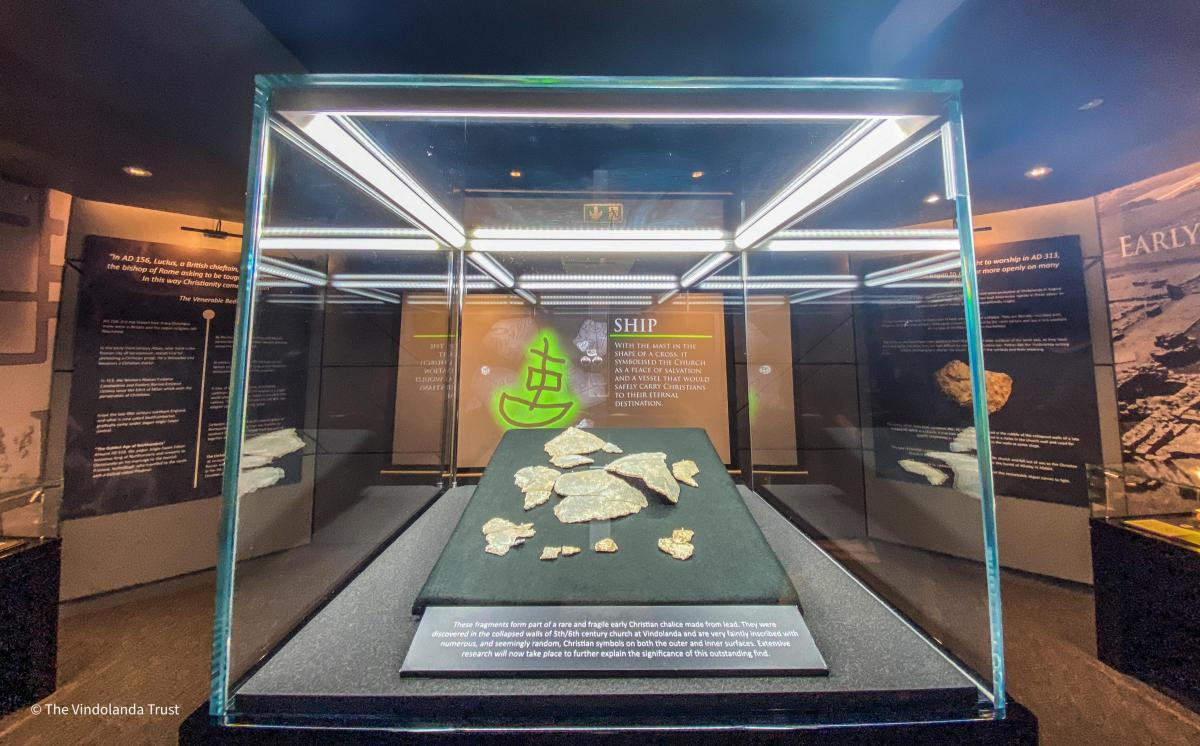

BURIED amongst a rubble-filled building, now known to be the remains of a 6th century church, 14 fragments of an incredibly rare lead chalice have thrown new light on early Christianity in Britain.

The discovery of the chalice, at the Roman fort of Vindolanda, near Hadrian’s Wall, has excited archaeologists because the fragments are covered in etchings – making it the earliest example of Christian graffiti on an object found in Britain.

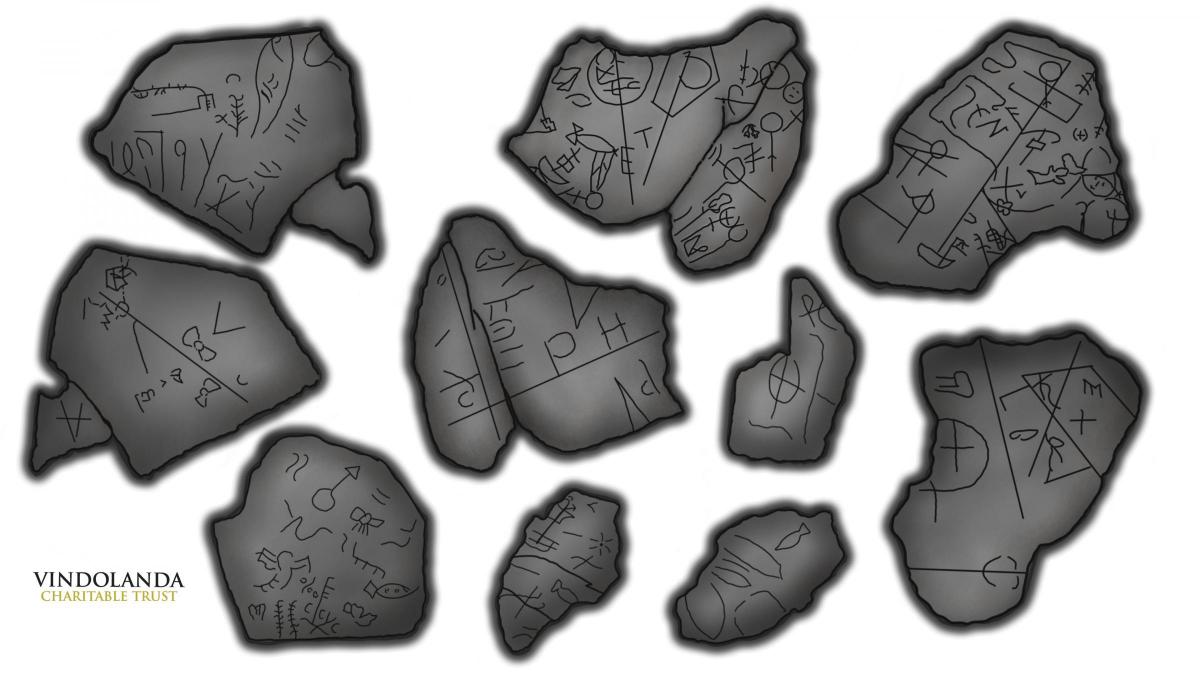

Although in very poor condition due to its proximity to the surface of the ground, each fragment of the vessel was found to be covered by lightly etched symbols, each representing different forms of Christian iconography from the time.

The combination of the etchings and the context of the discovery makes the artefact one of the most important of its type to come from early Christianity in Western Europe. It is the only surviving partial chalice from this period in Britain and the first such artefact to come from a fort on Hadrian’s Wall.

The etchings include symbols from the early church including ships, crosses and chi-rho, fish, a whale, a happy bishop, angels, members of a congregation, letters in Latin, Greek and potentially Ogam.

The marks appear to have been added, both to the outside and the inside of the cup, by the same hand or artist and although they are now difficult to see with the naked eye, with the aid of specialist photography, the symbols have been carefully recorded and work has started on a new journey of discovery to unlock their meanings.

Dr Andrew Birley, director of Vindolanda’s excavations, led the team working on the site of the discovery and is delighted by the significance of the find.

He said: “We are used to firsts and the wow factor from our impressive Roman remains at Vindolanda with artefacts such as the ink tablets, boxing gloves, boots and shoes, but to have an object like the chalice survive into the post-Roman landscape is just as significant.

“Its discovery helps us appreciate how the site of Vindolanda and its community survived beyond the fall of Rome and yet remained connected to a spiritual successor in the form of Christianity which in many ways was just as wide reaching and transformative as what had come before it.”

The academic analysis of the artefact is ongoing with post-Roman specialist Dr David Petts from Durham University leading research.

“This is a really exciting find from a poorly understood period in the history of Britain,” he added.

“Its apparent connections with the early Christian church are incredibly important.

“It is clear that further work on this discovery will tell us much about the development of early Christianity in the medieval period.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel