A LEADING health chief has called for questions to be asked on why Barrow is such a coronavirus hotspot as new figures showed the town is the 17th worst-hit in the country.

Dr Thomas Kane, the north west regional chairman for the British Medical Association, says it is “time to start asking why” Cumbria is experiencing disproportionately high rates of death and infection from COVID-19.

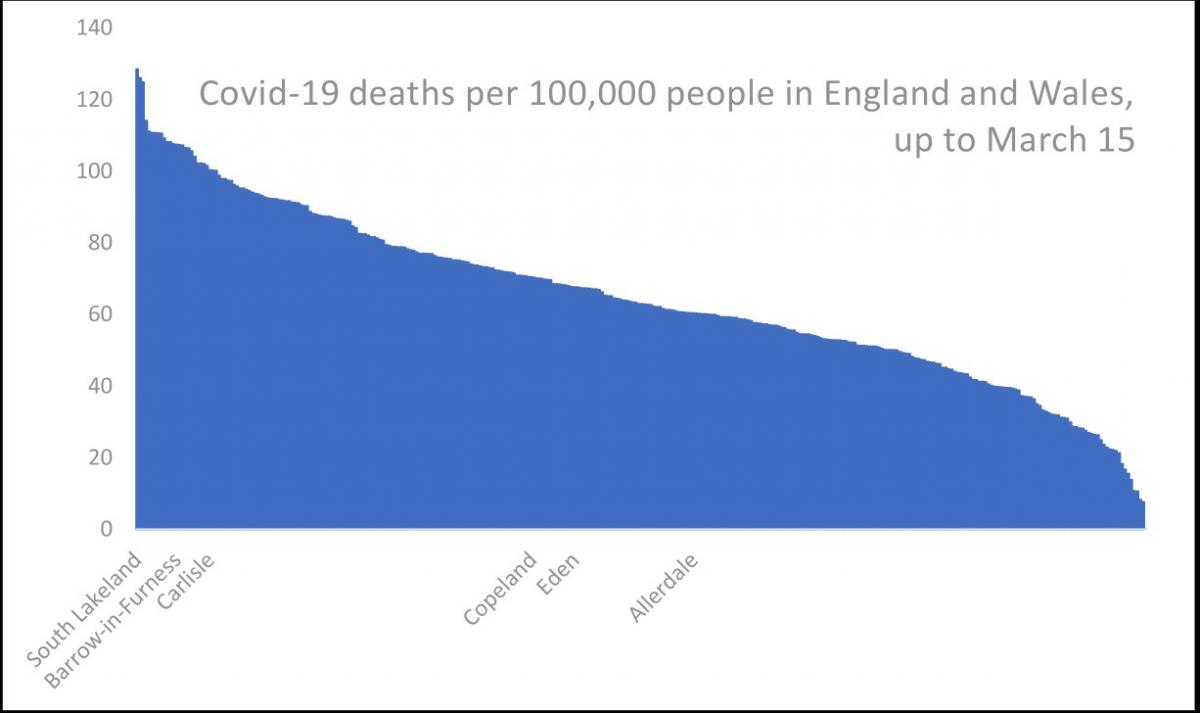

Dr Kane was speaking after new figures from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) showed Barrow has had more than 107 deaths per 100,000 people, making it the 17th-worst affected area in the country, just ahead of Sunderland and Solihull.

South Lakeland, which up to May 15 has experienced 128 deaths per 100,000 people, has seen the fourth-highest death rate from COVID-19 in all of England and Wales.

Hertsmere in Hertfordshire, encompassing towns like Borehamwood and Bushey, has seen the highest death rate, with 158 deaths per 100,000 people.

A Public Health England and local authorities report is being prepared into why the Furness area has high infection rates, as revealed in The Mail on Saturday.

Dr Kane said that while a number of reasons will likely be playing a part, the established link between higher rates of death from COVID-19 and higher levels of deprivation in an area must be urgently explored further.

“The Office for National Statistics has linked COVID-19 death rates to the affluency of an area,” he said.

“According to its figures, residents in deprived areas have experienced double the death rates of those in affluent areas

“Cumbria has 29 communities that rank within the 10 per cent most deprived of areas in England.

“As more data is published across the country about the impact of COVID-19, we are starting to see the impact it is having on vulnerable communities. There appears to be a link between health inequalities – those already suffering from worse health outcomes because of societal factors such as housing, education and employment.

“It is important that we continue to explore these links as further evidence emerges.”

Cumbria’s director of public health, Colin Cox said that the link between poor health and social deprivation was well established.

“Most health problems are connected to deprivation in one way or another,” he said.

He added this meant the response to COVID-19 has to take into account the fact that those who are least well-off are likely to be more at risk.

“We need to be especially vigilant about responding and identifying things in more deprived areas,” he said.

“We have to have eyes and ears on the ground in the more deprived areas to spot the outbreaks as soon as they might start, as soon as we possibly can.”

Mr Cox said it was too early to give a definitive answer on exactly what was driving Cumbria’s higher than average death rate.

“A substantial part of that is explained by our older population, but not all of it is,” he said,

“It looks to me as if there has been a slightly higher death rate in Cumbria than you would expect, even given the older population.”

Professor John Ashton, former director of public health for Cumbria, said that there are parts of the county which are especially vulnerable to the virus, given the higher rates of poor health linked to deprivation.

“The virus has really been able to pick out people who are unhealthy, unfit, overweight, have diabetes, and all the other risk factors that we know are to be found in particular parts of the county - particularly Barrow, which has one of the highest rates,” he said.

The ONS data is taken from official death registrations in which COVID-19 was mentioned as a cause of death.

One further coronavirus-related death was recorded at the Morecambe Bay hospitals trust over the weekend, taking the total to 162.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel