IN 1985, London’s Science Museum Library acquired illustrations of lead mining scenes on Alston Moor that caused a sensation among historians.

Because, for the very first time, they were looking at depictions of working life in the North Pennines during the time of the Napoleonic Wars.

Ian Forbes, for many years the director of Killhope Lead Mining Museum, has now pulled the early 19th century illustrations together in a book entitled Images of Industry: North Pennines Lead Miners in the Regency Period.

In a full-bodied introduction, he explains just why the watercolours and pen and ink sketches are so important. For starters, they are unique.

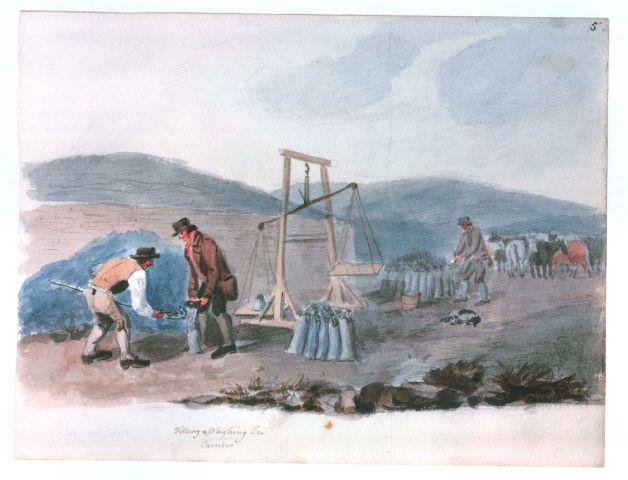

He said: “We saw sacks of lead ore carried on the backs of ponies and donkeys and could study the details of the saddles, the sacks and the scales used for weighing them.

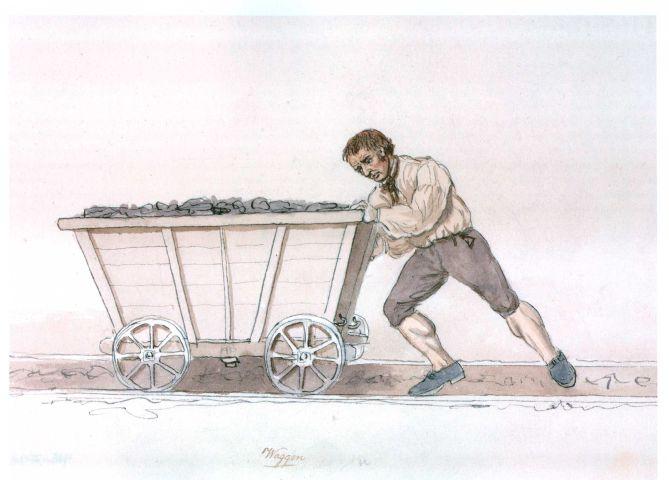

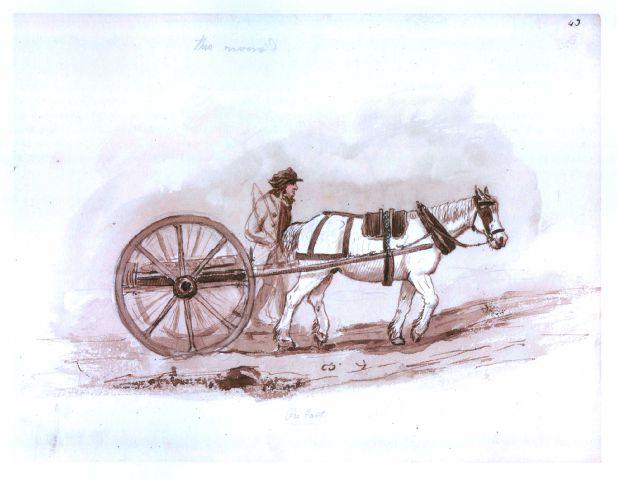

“We saw the two-wheeled cart used for carrying pieces of lead which we had known about from documents.

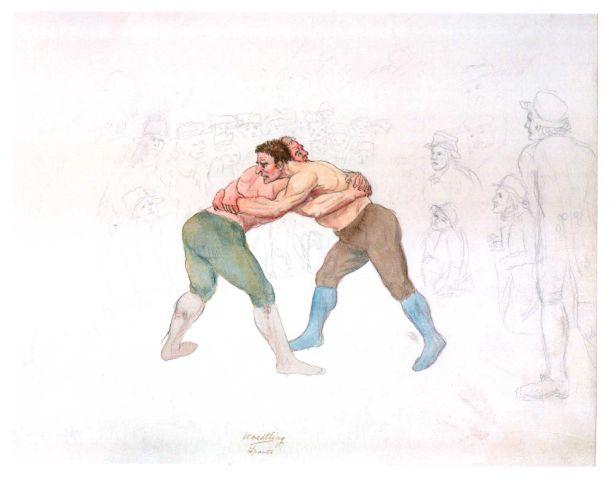

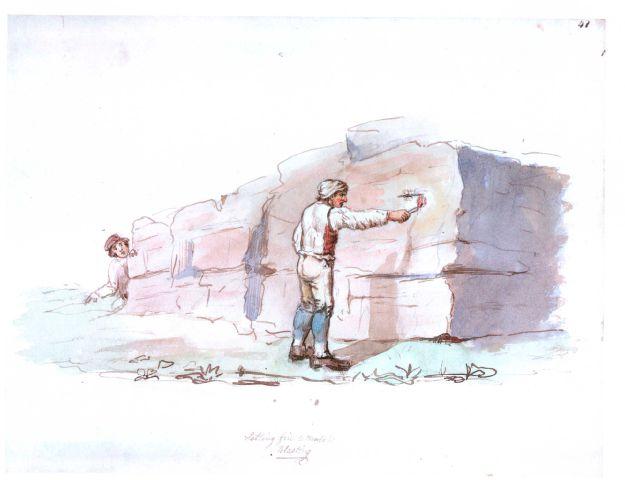

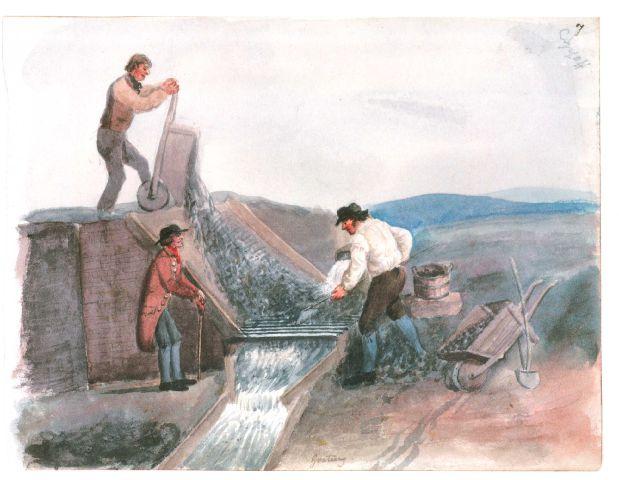

“We saw all the different stages and processes of lead ore washing, or separation, and we saw life in colour. Not the black and white past of early photographs, with their stiff, formal poses, but miners in brightly coloured jackets and trousers, talking or casually meeting, dogs at heel.”

In the 30 years since the collection was purchased by the library, it has become a rich vein to be mined for illustrations in exhibitions, leaflets, websites and on interpretation panels.

But never, until now, have they been brought between the covers of a single book and made so accessible as a whole to the wider public.

However, as his introduction highlights, the pictures have raised many as yet unanswered questions.

Who drew and painted them? Which locations, on the 1700 square kilometres of Alston Moor, do they actually depict? Who put the portfolio together and why?

Finally, who sold the collection in 1985 and where had it been in the 150 years or so since it was compiled?

Ian duly sets out on the investigative trail with all the tenacity of Sherlock Holmes.

Artistic techniques and the handwritten captions are analysed, the significance of what’s left out as well as put in discussed, and cross-references with illustrations in existing historic tomes explained.

And like any good detective, he bags his man. Or at least he identifies the prime candidate for the authorship of the illustrations.

As with any book that has a very specific and limited focus, Images of Industry will have a somewhat niche market. And with a £24 price tag, it is going to be the lead mining aficionado that dips his hand in his pocket.

But packed, as it is, with big, bold illustrations and descriptions that bring the daily grind to life, there is no doubting it is a very informative read.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here