FACING howling shells, clattering machine guns and vicious barbed wire, the soldiers of the First World War faced conditions unimaginable in the modern world.

They were expected to walk forward from mud-filled and rat-infested trenches into a solid hail of withering fire, with every chance of death or serious injury.

Yet for four long years they did just that, and it took a special breed of man to walk calmly into the firestorm created by the German machine guns and choking clouds of poisonous gas.

And thousands of those mud-caked and battle-scarred heroes came from Tynedale, swapping life on the farms, down the pits and in the offices of the district for the living hell of Flanders, the Dardanelles and beyond.

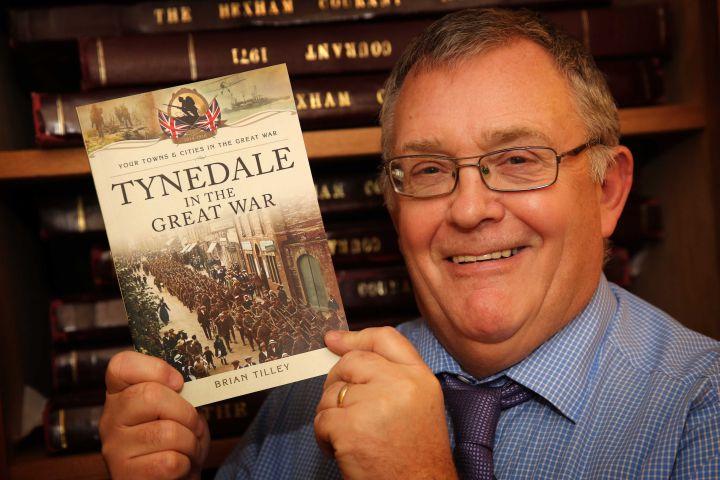

Their stories are told in Tynedale in the Great War, a unique record of how the district was affected by the War to End Wars, compiled by the Courant’s deputy editor Brian Tilley, which goes on sale tomorrow.

Its 150 pages are filled not only with tales from the trenches, related in letters home by servicemen hailing from everywhere from Allendale to Wylam, but also of accounts of everyday life on the home front, with concerns that Zeppelins were being guided on bombing raids by aliens living in Allendale, two little girls from Wylam being taken to court for selling home-made artificial flowers to raise money for the wounded without a licence and seven boys each getting six strokes of the birch for stealing a tin of corned beef at Prudhoe.

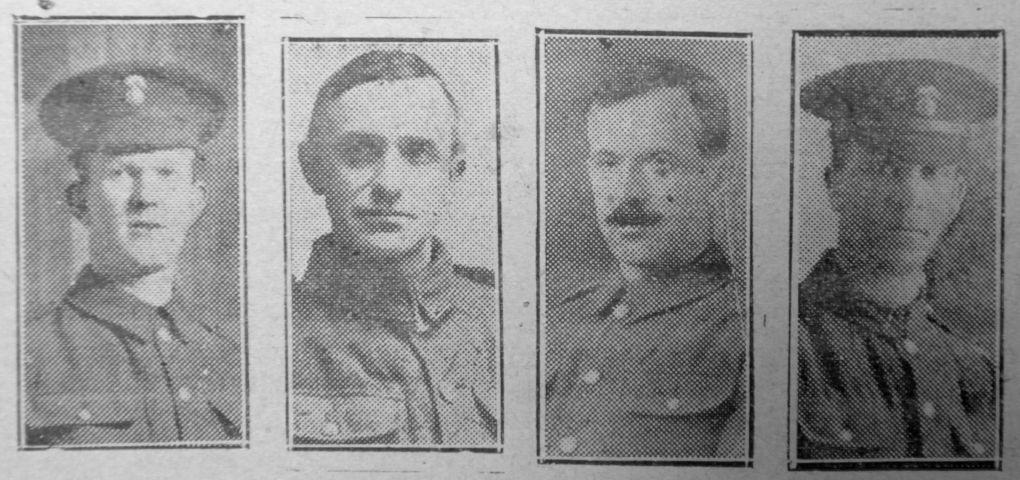

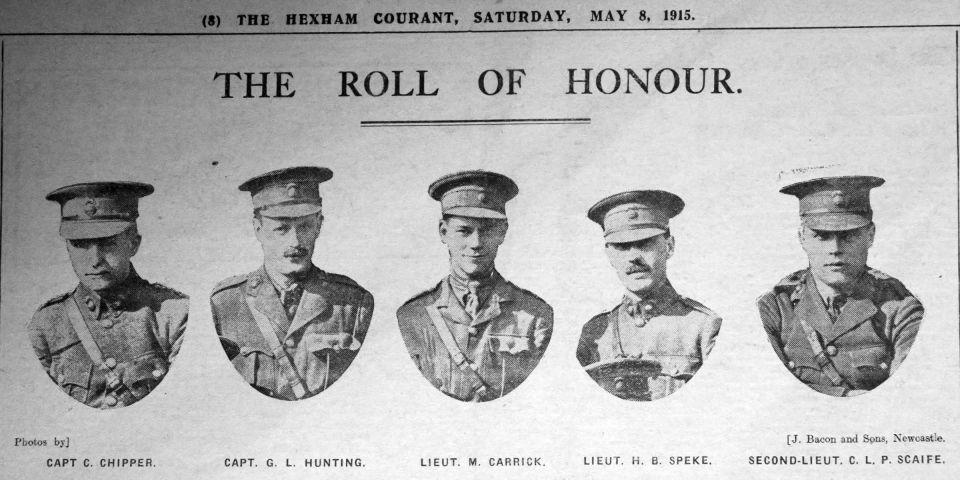

The book also features scores of photographs of moustachioed men in khaki and Royal Navy blue who did their bit for King and Country - as well as some of the recruitment posters used to shame more people into joining up.

Brian said: “Putting the book together, mostly from the 1914-19 files of the Courant, was a real labour of love, and what struck me was that even the tiniest of villages, such as Rochester, Birtley and Falstone, waved droves of men off to war.

“It was also fascinating to learn that a local woman was a survivor of the sinking of the Lusitania by a German submarine, as well as finding out that local women did a lot more than knitting socks for soldiers and wringing their hands.

“I also found the accounts of the military tribunals, set up to boost troop numbers in the latter stages of the war, very harrowing and moving.

“But there is lots of humour too, from accounts of mule races and cricket matches just behind the front line to the man opposed to turning the Hexham Abbey cloister into a vegetable garden, saying he did not want to feed potatoes with his own grandfather’s bones, as when he eventually crossed the Jordan, he might ask nasty questions!

“After the war, victory celebrations were held in virtually every village, but not without hiccups. A railway strike meant there were no fireworks in Hexham, so instead they lit huge flares meant to illuminate the English Channel, and an egg and spoon race had to be curtailed because of a lack of eggs!”

The grim fatalism shown by the troops was remarkable, with one Hexham officer, who played for Tynedale Rugby Club, dismissing a bad wound as “I’ve had worse hacks on the rugby field”.

Trooper William Metcalfe of the Imperial Yeomanry wrote that they were billeted at a farm where the farmer had fled because of the fighting.

He said: “As you can imagine, we are living like lords on poultry, pork chops and veal. Only one thing is missing; could you please send some smokes?

“Could you send me some Woodbines as soon as possible? English cigarettes are very scarce indeed. Our fellows have killed hundreds of Germans, but as quick as they are killed, others come up. I don’t think it will be long before this business is finished.”

And sadly so it proved for him, as he was killed in November 1914, when a shell scored a direct hit on the stable where he was tending his horses.

Another early casualty was Hexham’s Private Matthew Riley, serving with the West Riding Yorks Regiment. He was shot in the shoulder while fighting in Belgium, and returned home to a hero’s welcome.

He was met at the railway station by 240 members of the territorials, as well as a large crowd of the public, and was carried shoulder high to his home in Market Street.

Haydon Bridge village postman Private John Gray, of the Northumberland Fusiliers, wrote after being wounded at the Battle of Mons: “We were led into places which were sure death traps and had many a good starving for want of food and tobacco.

“Talking of tobacco, we had to smoke our tea. I smoked five tea allowances. We took tea out of the kettle and dried it on our trench tools.”

Reports were coming in from the front of Germany treachery, with the enemy accused of dressing in French and British uniforms and then launching surprise attacks.

A Tynedale officer wrote: “This sort of thing is a daily occurrence, and only makes things worse for the sausage makers when our infantry gets into them.”

Allendale’s Washington Blair, serving with the Coldstream Guards, wrote to his parents in December 1914 that the Germans appeared to be losing heart and the fighting was not as fierce as it had been.

He said: “I have been at the front for three months, and have only been wounded twice – once in the hand and once in the neck. I have lost two rifles, one bent double by shrapnel.”

Corporal William Civil, from Wark, wrote of shrapnel shells and bullets flying by like a drove of bees. He added: “Thompson Davison from Hexham had his horse shot from underneath him the other day. The German Uhlans (Prussian cavalry) are bad shots; he would have been killed if they had been any use.”

Trooper William Robson, of the Northumberland (Imperial Yeomanry) Hussars, wrote to his father in Hexhamshire: “It is fine sport shooting Germans; it is better than shooting rabbits.

“There are any number of shells flying about, but none of us has been hit with one yet, although one or two have bullet wounds. There are a lot of flying machines passing over our heads.”

Private J.E. Davison, of Holy Island, Hexham, wrote to his wife that he was the luckiest man living, having been hit twice in the chest by German machine gun fire.

He said: “I got a bullet right on the button of the left breast which flattened the button and broke my watch, and then got another on the top button. I thought my day had come, but the watch saved my life.”

A regular Courant correspondent throughout the war was a Northumberland Fusiliers officer known only as Tock, who wrote one August: “The Glorious 12th was a lovely day, and some of us couldn’t help thinking what a gorgeous day it would have been in the purple heather, waiting for the wily grouse.

“As it is, we have to content ourselves with shooting the Boche, which, being vermin, are never out of season. What we want is something to bolt them, so we can have a biff at the Boche in the open.”

Tynedale in the Great War is published by Pen and Sword, and is available from local book stores, price £12.99.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here