IT’S THE sort of brief encounter that today Alan Bennett or some independent production company would turn into a deliciously evocative vignette of times past.

Happily, the meeting between one of the most famous actors of his generation and the Bard of Redesdale in the middle of a snowstorm 100 years ago, almost to the day, was recorded for posterity – in the pages of the London Weekly News.

And thanks to Hexham Old Gaol volunteer Susanne Ellingham, who remembered the story unearthed by Tynedale historian John Smiddy, and the anniversary of its origin, we get to tell the tale again.

It happened one cold, cold night at the end of February 1917, when a blizzard cut off the road north over Carter Bar.

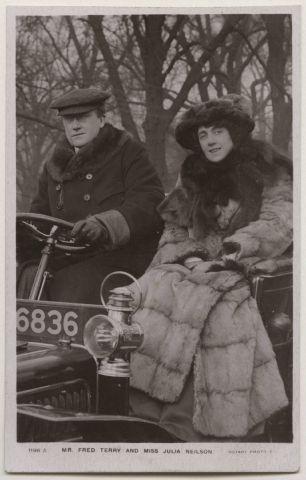

Fred Terry, scion of a famous acting family that included sister Ellen Terry, the greatest Shakespearean actress of her generation and Henry Irving’s leading lady, and two generations later, his great-nephew John Gielgud, was stuck.

He and his wife, Julia Emilie Neilson, a well-known actress in her own right, certainly weren’t going to reach Edinburgh that night in their chauffeur driven car.

With wonderful grandiloquence, the man who by then was famous for playing the Scarlet Pimpernel on the London stage described in his self-penned newspaper article their first impression of Low Byrness.

‘With the appearance of the evening shadows on, I am sure, the stormiest day the district had experienced for years, Miss Julia Neilson uttered a sudden cry of joy – just as a wrecked mariner might do if he sighted a sail.

‘“Don’t you see,” she said, pointing over the brow of a snow-capped hill. “There are two chimneys, and they are smoking. Surely here is warmth for us at last.”

‘With eager expectancy we sprang to our feet and, peering through the window, we gradually saw what appeared to be two small cottages on the roadside. With the rustling and the groaning of the engine and the car only bumping along at a snail-like pace we ultimately reached these lonely places of habitation.

‘“And now,” I said cheerily to my gallant comrades, “our troubles are over, I feel sure, for a little time at all events.”’

However, they received short shrift at the first cottage. As the middle-aged inhabitant opened the door, the eyes of a very hungry Terry caught the dozen or so delicious hams hanging from the rafters.

Explaining their predicament, and asking the man if he would kindly give them a meal, for which they were prepared to pay ‘any price the owner liked to name’, they were yet rebuffed. “We have got plenty of mouths here for the hams,” was the reply.

With a growing sense of desperation, the couple went to the next cottage, where this time they were met by a kindly-faced woman.

Her husband, a lengthsman responsible for keeping the road repaired and clear, was some miles distant helping to clear the snow, she explained as she ushered them to her fireside, but they were welcome to anything she could give them.

Terry said: ‘Before many moments had elapsed, the kettle, as the popular song goes, was singing on the hob and my wife was taking some nourishing cocoa, because she was rather distraught.’

When Billy Bell returned, Terry described him as ‘a nicer man you could not meet’.

Julia Neilson was tucked up for the night in the spare single bedroom in the little cottage, while Fred Terry and Billy Bell settled down for the night in armchairs by the fire.

In the London Weekly News, Terry wrote: ‘I enjoyed myself. Though the situation had looked very ugly, there was now something romantic about it all.

‘And, oddly enough, just as in the story of The Scarlet Pimpernel, a veil of mystery hung over my identity. I was like a Sir Percy Blakeney on a holiday. And unless Mr Bell reads these lines I do not suppose he will ever know who I happened to be.’

As the night and their conversation wore on, suddenly Bell asked his guest if he liked poetry, and would he be so kind as to read some of his poems aloud, ‘the better for Bell to observe any defects’.

Terry said: ‘I read through all the verses, which touched various subjects – the hills, the houses, the winding lanes, the horses and the cattle – and when I had finished, Mr Bell looked at me with admiring eyes, and said ‘You don’t read badly.

‘“No?” I said. “I’m very glad to hear that.

‘I must admit that it required a little personal strain to conceal a smile, but having a fair experience, as I think you will agree, of portraying the apparently unconcerned demeanour of Sir Percy Blakeney, I succeeded in doing so.’

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here