WELL-known phrases such as ‘signing the pledge’ and ‘going on the wagon’ have long been part of the anti-liquor lexicon – but from where did they emerge?

Over the past 12 months, Haydon Bridge resident Stan Owen has been delving into the Temperance Movement in Tynedale and has unearthed an interesting strand of local social history.

Next Wednesday, his curated exhibition about the Band of Hope will open at Bellingham Heritage Centre.

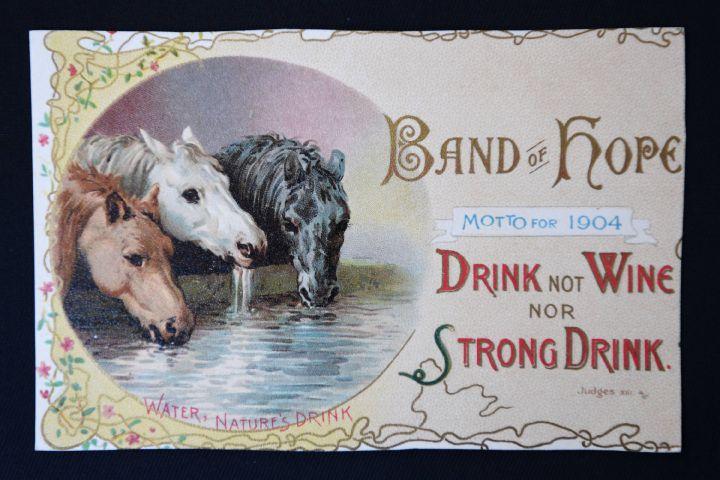

Stan’s curiosity about this organisation was pricked at one of the monthly antiques fairs at Hexham’s Wentworth Centre where he bought a batch of beautifully- coloured motto cards, many etched with gold, and bearing Biblical readings such as: ‘Look Not Thou Upon the Wine’ and ‘Be Strong and Hope to the End.’

He recognised the words ‘Band of Hope’ on them from the hours he’d devoted to scanning microfilms of local newspapers during his years as a local historian, and decided to investigate further.

The Band of Hope, he found out, was a response to the widespread, national concern from the middle of the 19th century that alcoholism had become an endemic problem affecting all sections of society.

“This was not perhaps surprising, since it was usually safer to drink beer from a brewery than water from what was often a contaminated well or pump,” Stan says.

“Something had to be done to protect the vulnerable from themselves and the evils of drink, which was seen as the greatest foe in Britain.”

In Jesuit-style, the idea was to catch them whilst still young and it was one Jabez Tunnicliff, a Baptist minister in Leeds during the 1840s, and a 72-year-old Presbyterian woman, Ann Jane Carlile, who began the children’s meetings.

Tunnicliff had promised a dying alcoholic that he would warn children about the dangers of drink, and whilst it’s unclear who thought up the name, Ann is reputed to have said: ‘What a happy band these children make, they are the hope for the future.’

The United Kingdom Band of Hope Union was formed in 1855 and 50 years later, the organisation boasted 3.5 million members. Queen Victoria became its Jubilee patron and it was part of the fabric of Victorian society and the Church.

Even in the upper reaches of Redesdale, within a year of its 1892 launch, the Band of Hope at the Birdhopecraig Presbyterian Church, under the legendary Rev. Thomas Newlands, had recruited 70 members.

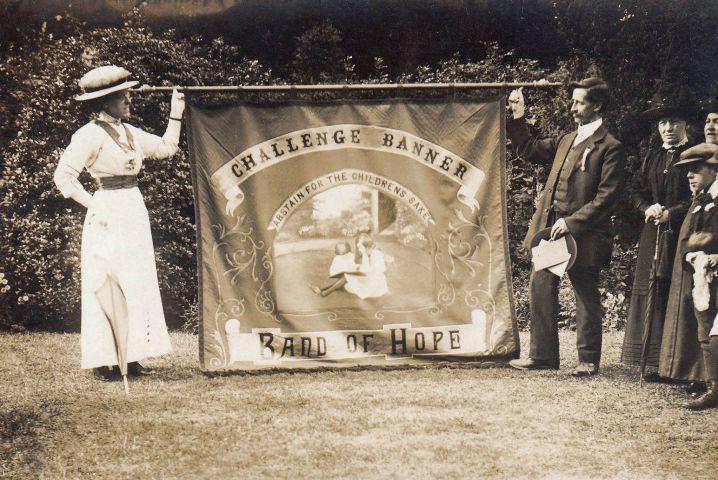

“The movement believed that the only way to promote temperance was to educate people against the evils of drink while they were still young, and many of their activities centred upon the church and its social events, such as Sunday School, picnics, meetings, demonstrations and marches with bands and singing,” Stan says.

There were talks and lectures, for which certificates were awarded for careful understanding or assiduous attendance, and Stan has some of these in his collection.

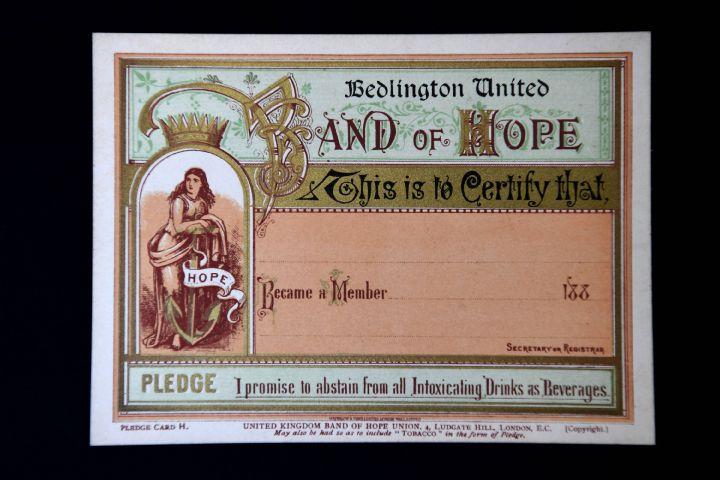

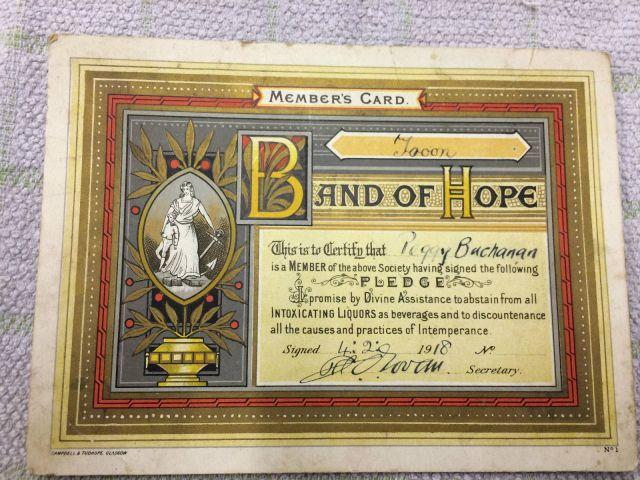

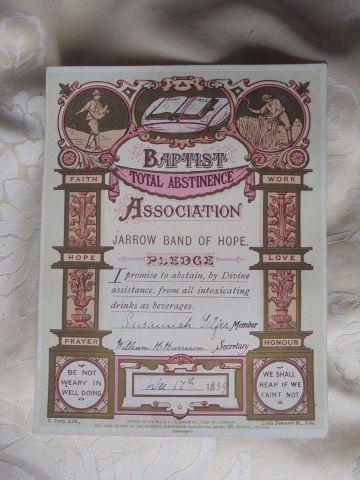

One certificate was presented to a certain Susan Telfer (1883-1898), daughter of a Stannersburn-born man, for passing an exam on the physiological effects of alcohol. But most important of all were the ‘pledge certificates’, usually framed for display, which were signed by Band of Hope members.

The pledge went as follows: “I promise by divine assistance to abstain from all intoxicating liquors as beverages.”

And as Stan observes, the ‘as beverages’ qualifier was important. “If someone fainted, brandy was all right.”

‘Demonstrations’ were a feature of the Band of Hope too and these involved speeches, singing, music, competitions and often a picnic in the country. Perhaps the wagons that were sometimes a part of these processions gave us the saying ‘going on the wagon’ – and indeed, ‘falling off’!

Although the Band of Hope had begun in the inner cities, it quickly spread out, and Stan says that almost every Northumberland village would have had a group.

Bardon Mill, for example, held a regular demonstration at Partridge Nest on the land of farmer Thomas Ritson (1833-1911), a supporter of Primitive Methodism and the Band of Hope.

In 1905, the Hexham Herald, reported on a Temperance Festival and Field Day at the village, where the Bardon Mill Temperance Band played and various temperance societies processed.

The day was addressed by a speaker from the United Kingdom Alliance, who explained that “the bones of the human body were made of two things, vegetable and mineral matter. Alcohol stopped the growth of vegetable matter and what stopped the growth of vegetable matter, stopped the growth of the body.”

The United Kingdom Alliance had been founded in 1853 for the suppression of liquor traffic and its first president was Sir Walter Calverley Trevelyan, who inherited the Wallington Estate in 1846. It was a post he held until his death in 1879.

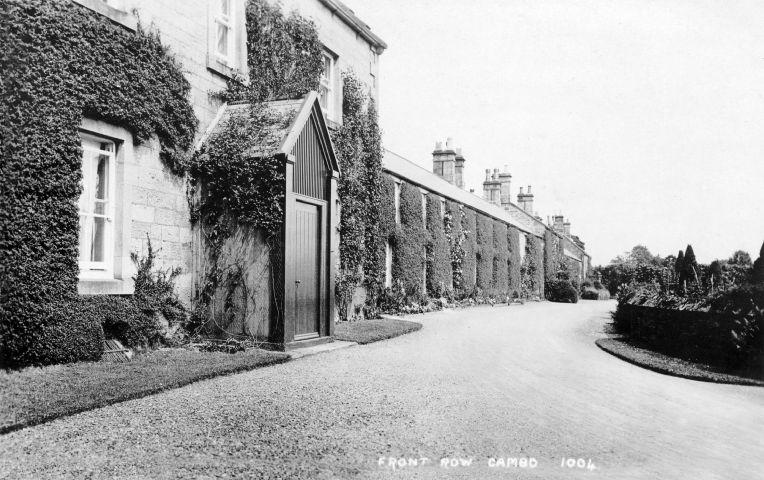

Stan says: “Many Victorian landowners were afraid that their workers were spending their wages almost immediately on drink and attempted to remove the temptation by making their estates dry.”

One can only imagine the response of Cambo’s drinkers when, on taking over the estate village, Sir Walter made it ‘dry’ by closing down the Two Queens Inn.

Cambo had a Band of Hope, but surprisingly, considering Sir Walter’s strong associations with the temperance movement, it wasn’t established until 1902.

However, it was probably one of the last to go, as it maintained a loyal band of followers until it closed with the death of its patron, Mary Katherine (Molly) Bell, Lady Trevelyan, in 1966.

Some Bands of Hope survived into the 1980s, but by the late twentieth century, there were more urgent social ills – hard drugs such as heroin and crack cocaine.

In 1996, The Band of Hope changed its name to Hope UK, and today it equips young people to make drug-free choices (including cigarettes and alcohol) and promoting healthy lifestyles.

* The Band of Hope exhibition is at the Bellingham Heritage Centre throughout May and June.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here