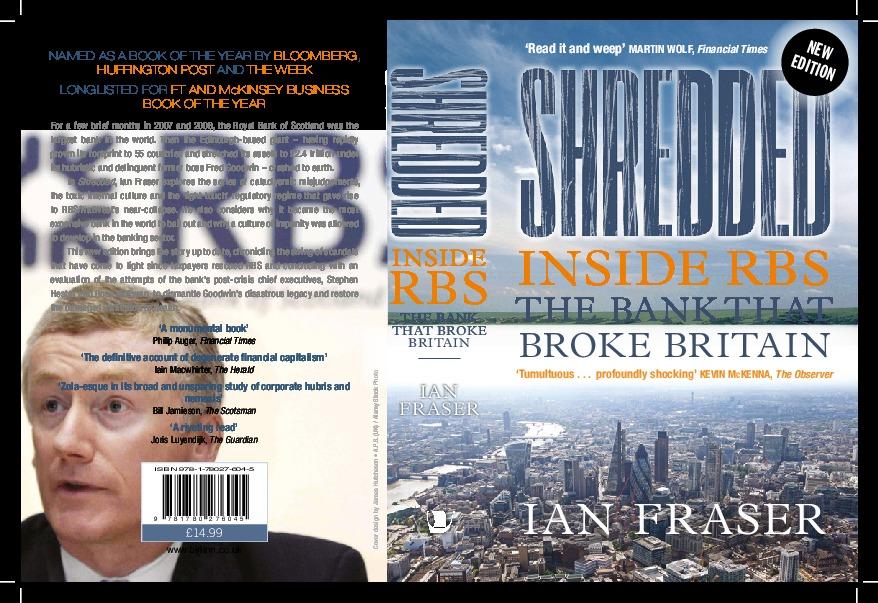

Shredded is more of a thriller than a book about finance, said sterling interviewer Chris Mullin.

And as if in confirmation, following author Ian Fraser’s talk there was a plethora of people to be found ensconced in Hexham coffee shops, pouring over their newly-purchased copies of the tome subtitled Inside RBS: The Bank that Broke Britain.

Award-winning journalist and broadcaster Ian Fraser proved to be the surprise hit of the festival with his forensic investigation into the collapse of the bank that was, for a few brief months in 2007 and 2008, the biggest bank in the world.

Initially rostered to speak in Hexham Library, his talk was moved to the Queen’s Hall Theatre when the tickets began selling like hotcakes.

The crunch date for the whole sorry story of the Royal Bank of Scotland was October 7, 2008, the day the then Chancellor of the Exchequer, Alistair Darling, took a call from the bank’s chairman.

The bank was going down. Fraser said: “Darling asked ‘how long can you keep going?’ and Sir Tom McKillop said ‘perhaps a few hours’.

“No-one was willing to help keep it going overnight, never mind a day or a week.

“Darling took fright. He had in his mind anarchy in the UK. He feared riots, blood on the streets, if people couldn’t get their money out.

“He decided he would throw whatever it took – to the point of almost bankrupting the country, if he had to – to bail out the bank.”

At that point, RBS had debts of £2.4trillion. By comparison, the UK’s entire gross domestic product was £1.6trillion. “If the bank had collapsed, it would have been the collapse of Britain.”

At its helm was the man nicknamed ‘Fred the Shred’, such was his reputation for ruthlessly slashing costs – Sir Fred Goodwin. Now plain Mr Goodwin, having been stripped of his knighthood, he is described as ‘a sociopathic bully whose achievements had been massively over-hyped’.

“He took pleasure in undermining colleagues and other senior RBS personnel in front of others,” said Fraser. “Sometimes they were so shocked, they were spotted wandering round St Andrew’s Square (outside its Edinburgh HQ), ashen-faced, because they didn’t know what had hit them.”

Under Goodwin’s leadership, the bank made more than 27 acquisitions between 2001 and 2007, while at the same time following a pattern of increasingly reckless lending. “They were looking at the types of things other banks weren’t doing, such as property developments,” he said.

A post-crisis report published by the Financial Services Authority in 2011 said far from focusing on the three pillars of banking – asset quality, leverage and capital – RBS was aping the ‘Greenspan Doctrine’ instead.

Greenspan, the chairman of the Federal Reserve, at the heart of the American banking system, from 1987 until 2006, was revered as some sort of financial guru, said Fraser. “His doctrine was that the use of derivatives eliminated risk.

“A derivative is a complex financial instrument which involves betting on the future value of items that could be shares or commodities.

“So a bank that had lent its money to residential home buyers, say, would bundle up these loans into a huge package of debt – that’s called the derivative – and then pass it on to another company, which could be an asset manager or an insurance company or whatever.

“The problem is, these packages can be opaque and include some real dross, so far from eliminating risk, they do the opposite, and that’s what happened in the American housing market.

“In 2001, Warren Buffet contradicted Greenspan – he said these sorts of derivatives were weapons of mass financial destruction.

“Buffet said you shouldn’t touch them with a barge pole.”

RBS certainly wasn’t the only UK bank to dive into derivatives, but it went in the deepest. By 2007/8 it was leveraged to the hilt, with liabilities 70 times the value of its assets. The failings weren’t Goodwin’s alone, of course, Fraser stresses. Politicians, regulators, rating agencies and a weak board of directors were all complicit.

HELEN COMPSON

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here