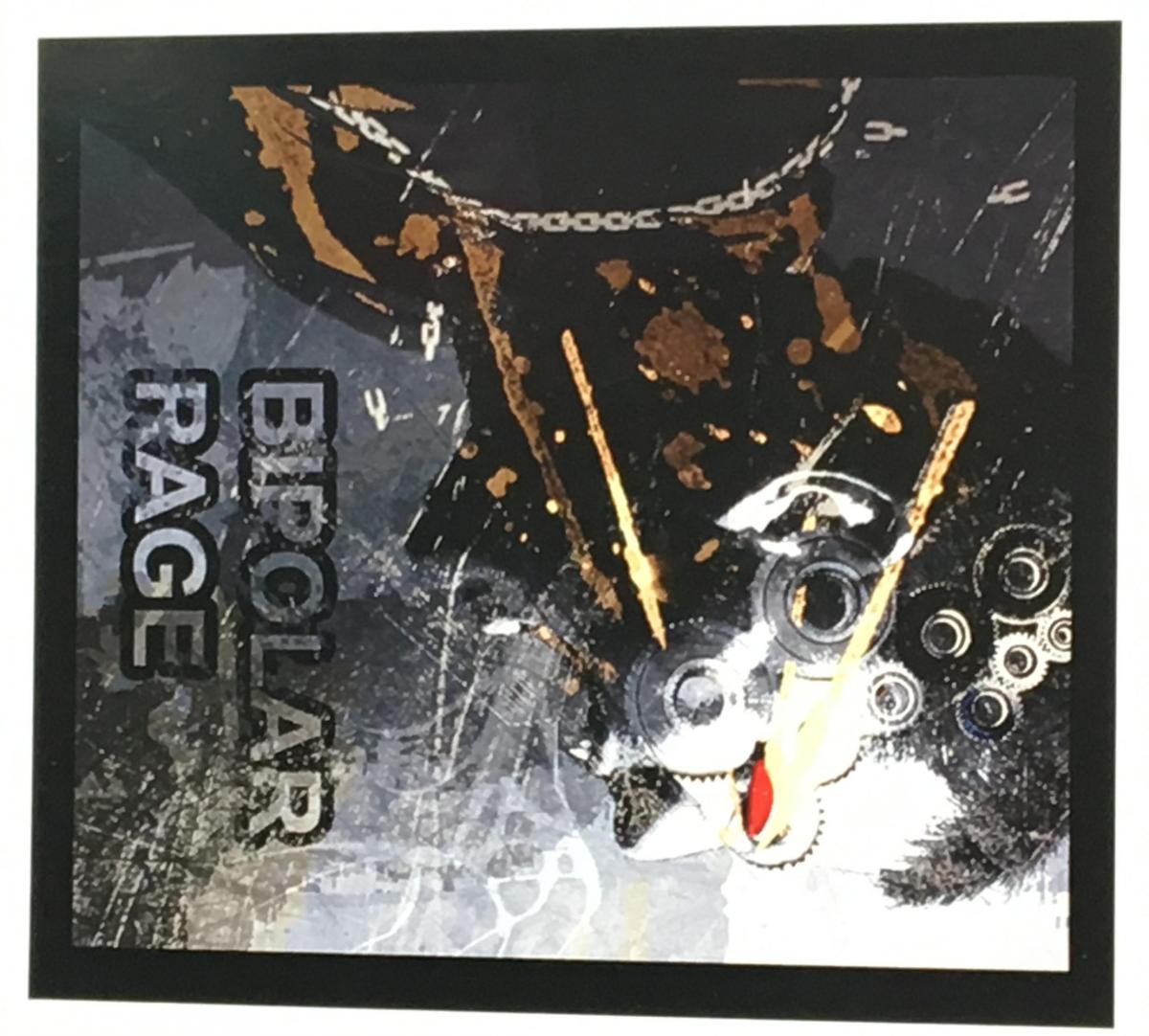

THE mental torture inflicted by bipolar disorder is there for all to see.

Bipolar Rage is just one of the pictures produced by digital artist Chris Lloyd in the months before he took his own life, at the age of 21, that depicts the torment – it exudes pain from every pixel.

It is currently hanging on a wall in Scott’s Café, in Hexham’s Forum Cinema, part and parcel of a wider exhibition of work mounted by the Tynedale branch of the Bipolar UK Support Group.

Chris’s mother, Judy Lloyd, launched the branch with two other people whose lives were affected by the disorder in the spring of 2014, a year after her son’s death.

It was needed to fill the void, create some means of social support in Hexham where none had previously existed, she said quietly.

If this group had existed when he most needed help, they would have accessed the support. Maybe things would have been different …

But getting to grips with this condition entails a massive learning curve, says Rebecca Steel (33), and an often equally long journey to diagnosis. “They say it’s 10 years before diagnosis of bipolar disorder and after that, it’s another three or four years to find the right medication.”

The difficulty is that it’s only when there’s a significant pattern of mood swings and behaviour to look back on that a diagnosis can be made.

Rebecca’s whole family – husband Carl and parents Vikki and Mark Coles – joined the Bipolar Support Group just a month after it was launched. Vikki doesn’t think her daughter would have had the confidence to walk through the door that first time without their support.

Vikki says now she looks back at Rebecca’s high school years and thinks the mood swings were probably caused by more than the teenage hormones that are usually blamed. “There wasn’t the awareness of mental health there is today,” says Rebecca.

Vikki remembers August 2013 as the start of the time her daughter’s problems really crystallised.

“That summer was horrible – you were so low,” she says to Rebecca. “I thought then ‘this is more than just about trying to read some self-help books.

“At the time, she was working full time and doing a university course and just trying to do too much. It was like she was on fast forward, ‘busy, busy’ all the time.

“Then she came crashing down at Christmas, when university broke up, and she went into a really depressive episode.”

Rebecca has experienced quite serious highs and lows for many years now, but they have become increasingly severe in the past three or four years.

Then, in that terrible depressive episode at the end of 2013, beginning of 2014, she began to hear voices.

That was when she was finally referred for assessment and diagnosis.

“I’d had periods in my twenties when I was very up and down, but it never clicked that it was bipolar disorder that was causing it. You just don’t, really.”

Judy certainly recognises the pattern. She had cottoned on quite quickly to what was happening to Chris, because she’d had a friend at university who was subsequently diagnosed as bipolar.

“When Chris started, it was with a mildish sort of down,” she said. “When he went into lower sixth form, I found him in his bedroom on the day he was going back to school and he was in tears, but couldn’t really say why.

“The following April, he suddenly started being very animated and jokey about nothing in particular, and going out very early, at five o’clock in the morning.

“I started to think ‘I have seen this before’.”

The thing Vikki stresses is that everybody’s experience of bipolar disorder is different – it is as unique as the individual. For some people, every day can be a series of rapid ups and downs, for others it can be a lower level rollercoaster stretching over weeks or months.

For some, the down periods can be long, black tunnels of despair. Vikki said: “That is very hard to see when you care for somebody. It’s difficult not to ask what’s wrong.

“Often they can’t explain what’s wrong, they don’t know what it is, so you just have to be there for them.”

Rebecca took a photograph recently that, for her, captures the essence of how she feels on her worst days.

It is in the exhibition, a picture taken from inside a cave, looking out. Framed in the distance, like a chink of light, is a lovely woodland scene.But the person who took that picture is shrouded in inky-black darkness.

“When I’m going down, it just feels like I’m walking into a dark tunnel,” she said, “and that’s when you start slowing down in yourself physically. You struggle to get out of bed.

“It can come on quite suddenly. You can wake up one day to find you are in this all-consuming depression.”

Are you frightened when you’re in that place, I ask. “Oh yes,” she says.

For those who experience the most extreme forms of mania, the great crests of euphoria, there is danger present.

Vikki says: “Their sense of boundaries goes. Some bipolar people spend their way into real trouble.

“They don’t feel the danger in some of the activities they choose either. It’s part of the illness – there is no safety valve.”

Judy agrees. “That’s right, they don’t anticipate the consequences of their actions. They can become very disinhibited too.”

While Rebecca doesn’t spend, spend, spend, she does understand the impetus that can drive people on into recklessness. “When you’ve been through a depressive episode and then mania descends, you grab it with both hands, because you just want to feel alive.

“You don’t think about the consequences. You don’t care about the consequences.”

Vikki is now one of the ‘facilitators’ of the Bipolar Support Group, which is designed for both sufferers and their families/carers.

Her primary aim is to raise awareness of its existence and to promote the fact that, crucially, help is at hand.

People need not be alone with this, she says. “The group is about sharing experiences and just being able to talk in a safe environment. It doesn’t matter what’s being said, you are not being judged.”

That goes for the carers as much as the sufferers. Rebecca says husband Carl has drawn as much support and reassurance from the group as she has.

The Tynedale branch of the Bipolar UK Support Group meets on the third Saturday of every month, between 11am and 1pm, at Hexham Community Centre, on Gilesgate.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here