THE way Elizabeth Crewe discovered her husband was gay just wouldn’t - couldn’t - happen today.

But we’re talking about the 1970s, so the stringently politically correct times we live in today were light years away.

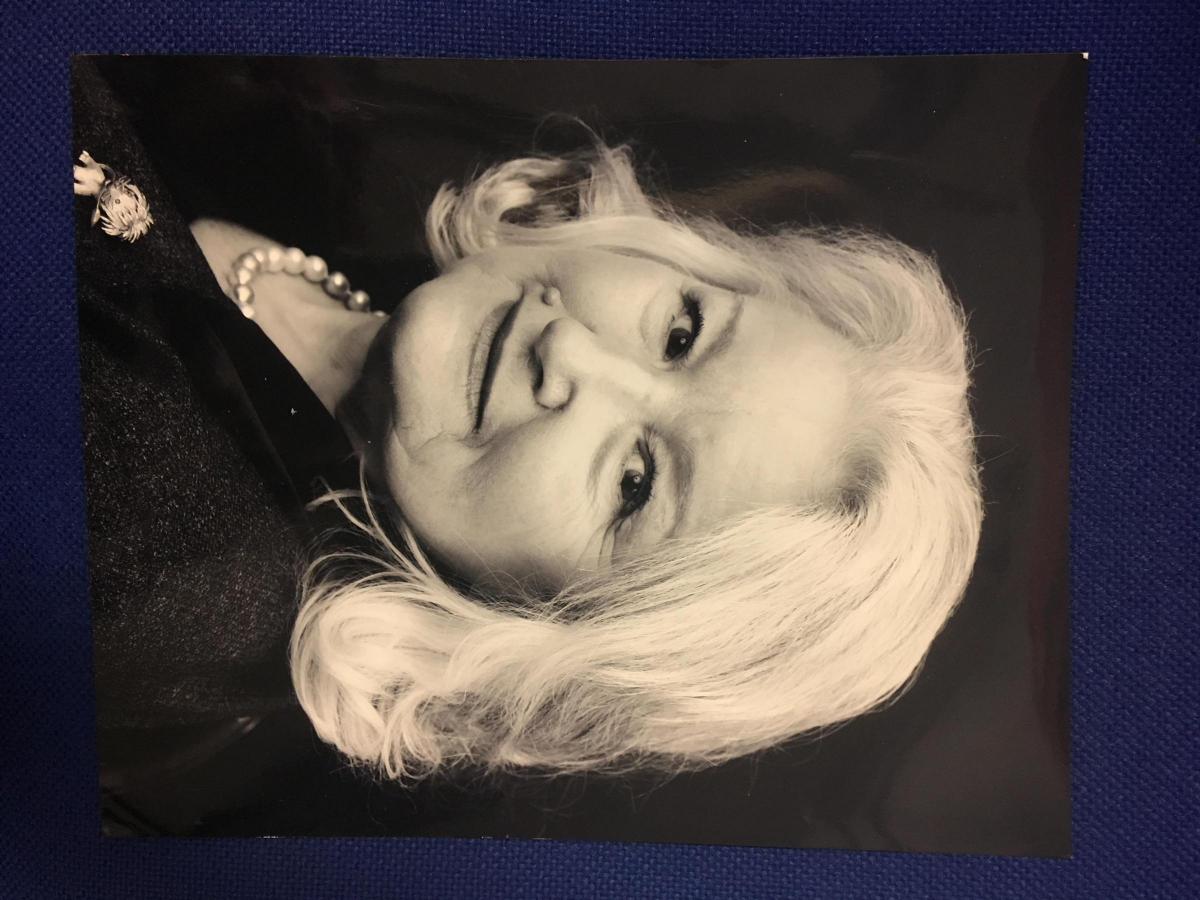

Elizabeth, a retired actress who has now written a novel that is the thinly disguised story of her own life, recounts in her own inimitable style the real-life telephone call that suddenly made sense of her miserable marriage.

“He’d ‘come out’ in 1972 apparently, but he didn’t tell me - of course, homosexuality had only been legalised at the end of the 1960s/early 1970s,” she said.

“It was still a taboo subject in 1976, the year he went in for a hernia operation, and apparently the surgeon had come out of theatre and said in front of the whole medical team ‘somebody’s been a naughty boy’.

“The theatre sister was a friend of mine, so she rang me … “

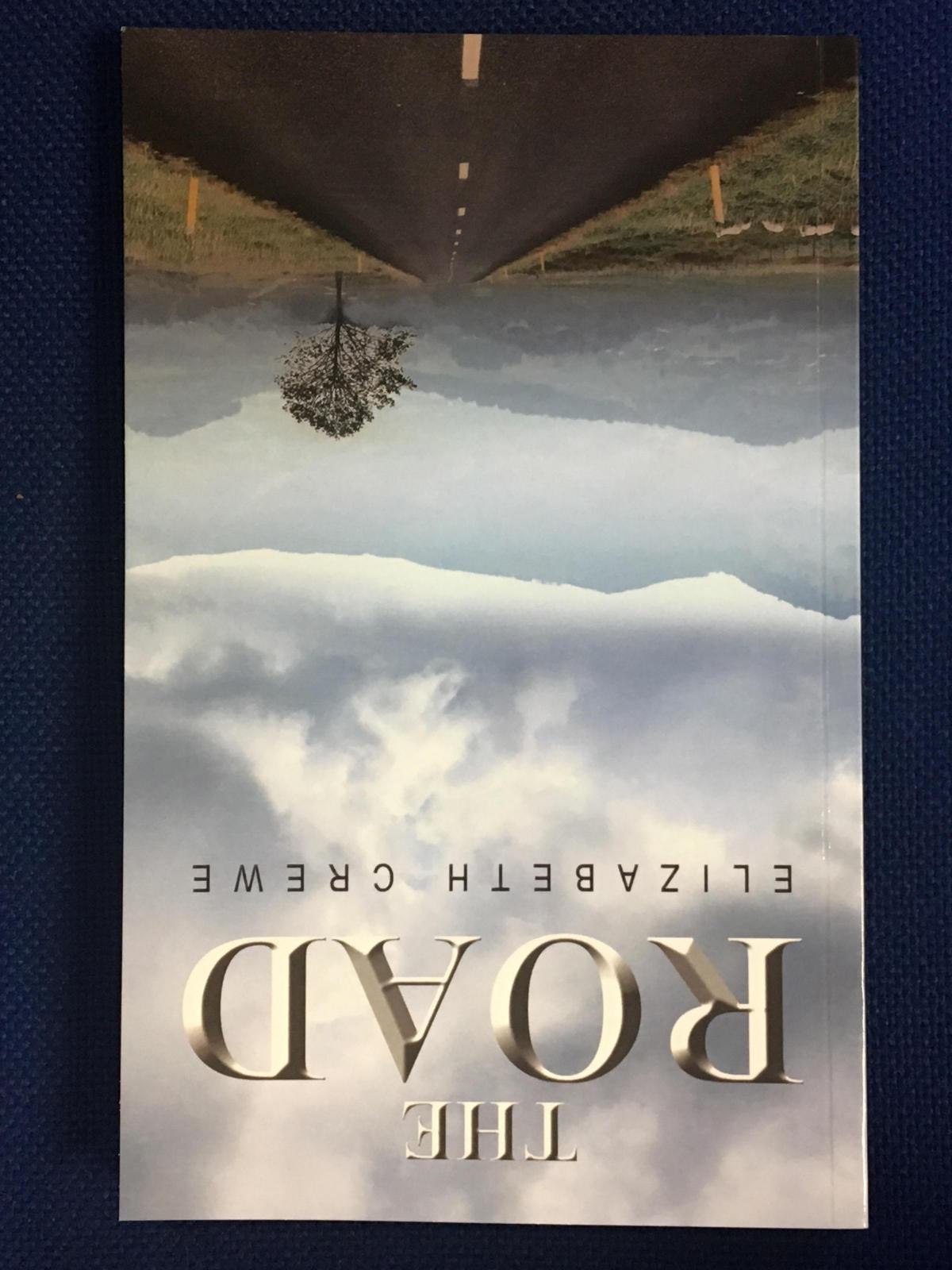

In The Road, her book published by Austin Macauley, her main protagonist is sitting down in front of the fire with her granddaughter on the eve of the latter’s wedding. Their conversation opens a door onto the past.

Elizabeth herself says she was motivated to write the book because, while there has been a lot in the press in recent years about men who were trapped in false lives, there has been nothing about the wives imprisoned with them.

“Austin Macauley wanted to set me up with a website, but I said no, because of the controversial nature of this book,” she said.

“I’m looking at homosexuality from a heterosexual wife’s point of view.”

The 1970s ushered in the dawn of a new era in terms of sexual freedom, but of course it also represented a huge break with the past.

Elizabeth said: “When I told my father was my husband was homosexual, I could look at it as an illness that had to come out and must be discussed and the situation sorted, but my father couldn’t accept it.

“He saw it as an affront to my femininity - he still saw it as totally illegal and totally wrong.

“I think a lot of the problems we have today come from the fact there are still some generations who are completely homophobic.”

Her father, Norman Himsworth, was not a man to be reckoned with though. He was most definitely old school - and a spy with MI5 to boot.

A chronic asthmatic, he was exempted from joining up during the Second World War and remained in his job as a journalist, until naturalist, broadcaster and later famed spymaster Maxwell Knight recruited him.

Elizabeth said: “Father was a wonderful raconteur and very interested in the law. He was recruited by Knight in about 1940 and remained in MI5 right up until 1998, by which time he was what was known as a ‘retread’, acting as a consultant and training others.

“He was recruited with John Bingham, Victor Rothschild and Bill Younger, who was also my godfather. The BBC did a programme about them called The Gentleman Spies not long before my father died.”

Just like her main protagonist, Elizabeth today is looking back on a life few of us can imagine, but from a safe and comfortable distance.

After a second, relatively lengthy marriage to somebody who turned out to be a serial philanderer, she is now married to her third husband, Richard, and happily settled in a lovely, old, rambling hall in the rural environs of Humshaugh.

I say ‘settled’, although they only moved in at the beginning of September – from their previous abode in Callaly Castle, near Alnwick, and the builders/decorators are in.

But the rooms where the work is taking place are so far away from the kitchen and its two morning rooms that we sit in peace, chatting, with me looking out of a window that frames just one of the many chocolate-box views of the fabulous garden.

She says, quietly, that besides allowing her to pick over the coals of her first marriage, writing the book has also given her the space and time to grieve for the daughter she lost just as the rest of her life was breaking up.

When Elizabeth fell pregnant with Emma a year after her first marriage, in the mid ‘60s, she already knew she’d made a spectacular mistake in getting married in the first place. “I realised I’d made an even worse mistake, having a baby by him, but you know, by then I’d made my bed and I just had to lie on it.”

She had a second daughter, Luceika (“but she’s always known as Squeaks”), by him in 1970, despite living in the hell of a loveless marriage. “The girls only happened because he came home absolutely tipsy on two occasions,” she says with a laugh.

Tragedy struck when Emma was 11. “I’d taken the girls up to my grandmother’s in York – it was her 90th birthday,” said Elizabeth. “I left them there while I went back down to Buckinghamshire to work, but after a couple of days my aunt rang me and said ‘Emma’s not well, can you come back up – the doctor wants to see you’.

“This was in the March and in the February I had noticed that Emma seemed to have lost her appetite and she was lethargic.

“It suddenly came to me. I said ‘yes, I know, she has cancer’. To this day I don’t know where that came from or why I said that.”

When Elizabeth asked the doctor ‘how long?’ his answer was ‘days’. In the end, she lived another nine weeks, in hospital. “She was just coming up to her twelfth birthday. She died of leukaemia in the May and would have been 12 in the August.”

Amid the debris of her failed marriage and with her younger daughter to support, Elizabeth had no choice but to go back to work.

She dusted down her secretarial skills initially and got a job with the Ministry of Defence, but then several years down the line, opportunity came knocking.

A keen amateur actress and an ad hoc professional singer, she was asked by Frieda Kelsall, a television scriptwriter and the founder of The Bridge theatre company, if she would like to join the Sheringham Little Theatre in Norfolk for a season.

It was the start of many happy years treading the boards with repertory theatre, during which she criss-crossed the UK and Europe in a succession of character roles: Olive Harriet Smythe in Move Over Mrs Markham, Mrs Slack in Sailor Beware, the eponymous role in The Merry Widow, the Duchess of Berwick in Lady Windermere’s Fan, and many more besides.

They were good years. Elizabeth had attended the Guildhall School of Acting before capitulating to her father’s demand she learned a useful skill. Finally, she was pursuing her dreams.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here