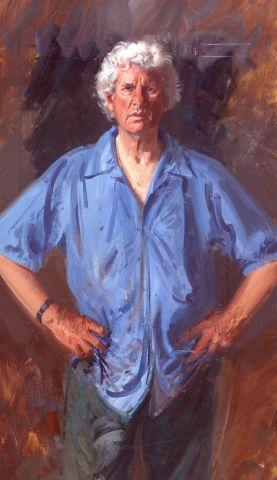

ANDREW Festing, portrait painter to royalty and aristocracy, has a lineage as notable as that of many of his subjects.

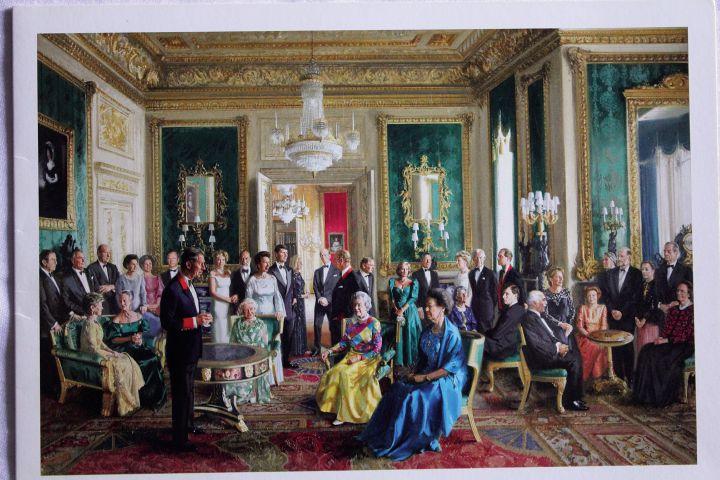

One of Britain’s foremost portraitists, his thousand or so ‘sitters’ have included the Queen (several times over), the late Queen Mother, Princess Anne, many a member of the House of Lords and the luminaries of Lord’s Cricket Ground.

While he spends his weeks painting in his studio in London, his weekends are mostly spent at his family home in Colwell.

In a big, bold, beautifully illustrated new biography, Andrew Festing: Face Value , author Jenny Pery says his meteoric rise to the top of his profession is all the more remarkable considering his late arrival on the scene – for his famous father had insisted he follow in his footsteps, into the army.

“This paternal command made any art training impossible,” said Ms Pery, “and as a painter Festing is entirely self-taught. Perhaps this fact accounts for the freshness of his portraiture. He has had to find his own way and his own solutions to the problems of representation.”

But what is also evident is that long before he ever picked up a paintbrush, Andrew Festing already felt right at home in some of the great houses of the land – the key, surely, to his relaxed and assured approach to the most formidable of commissions.

For anyone who doesn’t already know who the Festings are, Ms Pery sets the scene in chapter one.

Andrew’s father was Field Marshal Sir Francis Wogan Festing, who counted Chief of the Imperial General Staff among his many titles, and his mother, Mary Cecilia Riddell, of Swinburne Castle.

He and his three brothers can look back on a proud and illustrious line of military ancestors.

They include a captain killed at the Battle of Blenheim, a commander at Waterloo and a couple of admirals, just for starters.

Andrew’s great grandfather, another Sir Francis Wogan Festing – this time a major general and aide-de-camp to Queen Victoria – was awarded the Legion d’Honneur for his deeds at the Siege of Sebastopol.

His grandfather, Brigadier-General Francis Leycester Festing, was wounded twice fighting in the Boer Wars and the First World War, while his four paternal great-uncles won eight Distinguished Service Orders between them in the latter.

Andrew’s maternal family, meanwhile, distinguished themselves in another sphere. Mary Riddell was descended from the de Ridels who fought alongside William the Conqueror at the Battle of Hastings.

From the early 1300s onwards, they had been Sheriffs of Northumberland and Mayors of Newcastle and counted vast Northumberland estates among their possessions.

They were also one of the North’s leading recusant families and counted among their ranks the Blessed Sir Adrian Fortescue, who was martyred in 1539.

Mary Riddell herself was Catholic to her very core, devout and completely unquestioning in her faith, while Andrew’s father had all the religious fervour of a convert.

Today, Andrew’s youngest brother, Matthew, is the Grand Master of the Order of Malta and, ranked as a prince in the Catholic church, styled His Most Eminent Highness. Fra Matthew is the highest-ranked officer after the cardinals and the only other leader after the Pope – the sovereign of the Vatican – who has the status of an independent monarch of an entity within the Catholic Church.

Andrew Festing: Face Value begins with a fascinating account of the Festing brothers’ childhood, during which the countryside surrounding their rambling manor house of The Birks, in Tarset, was by turn a refuge or an adventure, depending on which parent had sent them forth.

They would hide out in the hills and woodland for days at a time when their largely absentee father, who was feared and disliked in equal measure, reappeared. (In fairness, the adult Andrew did appreciate his father was an interesting man with a sharp sense of humour.)

And the countryside was their mother’s chief resource. First thing in the morning, she said ‘don’t come back till lunchtime’ and after lunch, ‘don’t come back till teatime’.

Ms Pery wrote: “Mary Festing was not interested in her boys’ education, wanting nothing more for her sons than the chance to live a country life and serve Mass.

“She engaged a series of governesses, including a Miss O’Shaunessy, who had a wooden arm with which she used to whack the boys.”

It is details like this that bring the book to life, that make it so very readable.

The memories, the flashes of humour and the raw honesty about a life less perfect make it accessible for the man on the street. No rose tinted specs here – the people are real.

There’s a chapter on the nine years Andrew, denied his request to go to art college, spent in the army. It did have its recompenses.

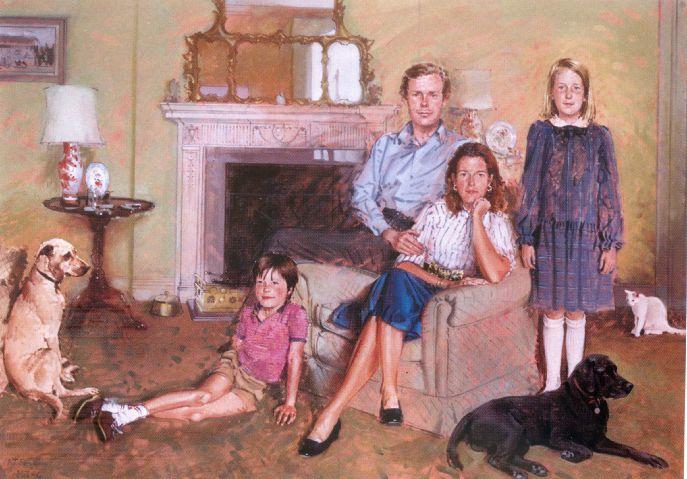

Having been appointed aide-de-camp to General Sir Richard Fyffe, who served in the same regiment as his father, Andrew promptly fell for one of the general’s daughters.

He and Virginia (‘Ginny’) Fyffe were married in 1968, despite a mix-up that was an entertaining saga (at least for the reader) in itself.

There’s another on his subsequent career as a valuer with Sotheby’s, a job he won on the grounds that he had a car.

He was taken on by the head of the paintings department, John Rickett, a brilliant art historian and an expert on the Victorian fairy painter Richard Dadd. Ms Pery said: “(Rickett) eventually descended into madness just as his favourite painter had done, once coming into the office with a loaded gun.”

It was during his time at Sotheby’s that the true extent of Andrew’s artistic talent became apparent.

In any other milieu, he would probably have been of interest to the police as an expert forger, but as it was, he made his mark painting exact replicas of some of the valuable pictures about to go under the hammer – a sort of consolation prize for clients needing the dosh being forced to sell off prized works of art.

That led on to the next (and current) chapter of his life and the plethora of commissions that came his way. As the book shows, they are the colour in the rich tapestry that is his life.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here