IT IS 30 years this year since Pan Am Flight 103 blew up over the small Scottish town of Lockerbie, and ever since, Jean and Barrie Berkley have been searching for answers.

Mostly, who really killed their 29-year-old son Alistair and the other 258 people on board?

Eleven people also died on the ground that day in 1988, as the components of the Boeing 747 ‘jumbo jet’, blown apart by a bomb hidden in a radio-cassette player, rained down on the housing estate below.

It was December 21 and Alistair was on his way from London to New York to stay with his parents for Christmas. Barrie was working on a three-year contract there for Mobil Oil.

Jean remembered: “I was doing the ironing, watching the television, and saw the news flash showing pictures of the crash, bits of the plane on fire in Lockerbie.

“I said to Barrie, ‘what plane is Alistair on?’ I didn’t know it was Alistair’s plane.”

Barrie says simply: “I did. I knew it was his flight.”

In the weeks and months afterwards, as the numbness of the grief began to thaw a little and the questions began, the families of the 31 British people on board laid the foundations for the pressure group UK Families Flight 103 that has been digging for the truth ever since.

For unlike the American families affected, the UK group has never trusted the verdict of the special sitting of the Scottish High Court of Justiciary – held on neutral territory at the former US Air Force base Camp Zeist, in Holland – that sentenced the only person ever convicted for the atrocity to life imprisonment.

The trial and some of the evidence produced was fundamentally flawed, says UK Families, and they believe Abdelbaset al-Megrahi was innocent.

Barrie said: “The significance of the trial to the Libyans was that if they accepted the blame, and accepted that one of their men had blown up the plane, as long as they paid compensation, the UN sanctions against them would be lifted.

“So they had a motive for sacrificing their man.”

They are not alone in thinking Megrahi was thrown to the wolves, and now the Scottish Criminal Cases Review Commission has given the green light to an application from Megrahi’s family for an appeal – a review of the case against him.

In life, he had lost one such appeal in 2002 and then dropped a second in 2009 when he became ill.

A spokesman said last week: “Having considered all the available evidence, the commission believes that Mr Megrahi, in abandoning his appeal, did so as he held a genuine and reasonable belief that such a course of action would result in him being able to return home to Libya, at a time when he was suffering from terminal cancer.

“On that basis, the commission has decided that it is in the interests of justice to accept the current application for a full review of his conviction.”

As they look out over the idyllic countryside surrounding their Sandhoe home, Jean (88) and Barrie (91) pray that this time the truth will out. “There are too many people who don’t want the answers to come out, but we have to remain hopeful,” said Jean.

UK Families met monthly in the early days, but now it’s twice a year and always in Coventry, the most central place for members.

Among them, Jim Swire, who lost his daughter Flora (23), travels up from his home in Oxfordshire, and John Mosey, who lost daughter Helga (19), down from Cumbria. Between them, these two men sat through every single day of Megrahi’s six-month long trial.

The Berkleys attended for two weeks in total and were present for the verdict. “There were several faults with the trial,” said Jean.

Barrie goes to his study and comes back with a copy of Megrahi: The Lockerbie Evidence, written by researcher and television producer John Ashton. The strapline enshrines its raison d’être: ‘You are my jury’. Readers can weigh up the case for themselves.

Just how did this head of security for Libyan Arab Airlines, and alleged undercover agent with the Libyan intelligence service Jamahiriya Security Organisation (JSO), become the world’s most wanted man – accused of the murder of 270 people in what was simultaneously the worst ever aviation disaster and the biggest criminal inquiry in UK history?

At the heart of this complex case is the unaccompanied brown Samsonite suitcase, containing the bomb, that was loaded onto a plane in Malta. It was tagged for the Pan Am flight 103 from London to New York, so at Frankfurt, it was transferred to Pan Am feeder flight 103A to Heathrow and then onto the doomed jumbo jet.

The kernel of the case against Megrahi was that he was in Malta that December and knew airport systems well enough.

The case had been packed with clothes and an umbrella bought at a specific shop on Malta and the shopkeeper subsequently identified Megrahi as the person who’d bought them.

Jean said: “It later emerged the shopkeeper had been paid $2m by the Americans to say he could remember Megrahi entering his shop to buy the umbrella, because it was raining.”

Barrie continues: “But when the weather records were studied it was found it hadn’t been raining that day, and Megrahi was still saying on his death bed that he’d never been in that shop.”

Also key to the case was the unusual timer that activated the bomb, said to have been one of a batch of 20 made by a Swiss company called Mebo and supplied exclusively to JSO.

“Lots of fresh evidence has come out since the trial,” said Barrie. “A piece of circuit board belonging to the timer from the bomb was examined by Sheffield University metallurgical department and they said the metal used was not the same as that used in the circuit boards the Swiss company supplied to Libya.”

It is believed in many quarters that the Pan Am attack was actually carried out by Iran in revenge for the mistaken US Navy strike on an Iranian passenger jet six months earlier, in which 290 people died.

An Iranian defector has gone on record as saying the Lockerbie bombing was ordered by Ayatollah Khomeini and carried out by a Syrian terrorist group paid millions to bring down a US commercial airliner.

The reasoning goes that, keen not to antagonise Syria, then an important ally in wrangles with Iraq, the US and UK governments colluded in Libya taking the blame. Libya, after all, was desperate to end crippling UN sanctions and begin negotiating lucrative oil deals.

Jean said: “We’ve been in touch with the Peace Studies Department at Bradford University and one of their staff, Davina Miller, has a longstanding interest in Iran.

“She has got hold of a lot of material that shows the CIA really believed it was Iran responsible for Lockerbie and that it was the FBI, directed by the US government, that switched attention to Libya.”

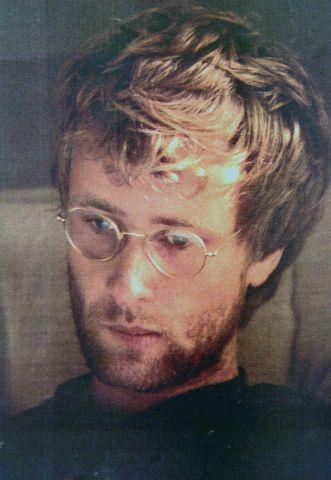

What this quietly spoken, but indomitable, couple do know for sure is that Alistair’s death has had a devastating impact on their family. “He’s left a hole in our lives,” said Jean. “He was such an active, dynamic person.

“His death was shocking enough, but it is just as shocking that there is this level of manipulation of evidence on an international scale. It undermines your faith in people and human nature. It is an insult to his life and death.”

Alistair was actually booked on a flight later in the week, but then rang them to say, surprisingly considering the usual Christmas rush, there were plenty of free seats on this particular flight. He’d been able to reschedule.

It is now known that due to a warning rung in to a US embassy, America was aware that a Pam Am flight was going to be attacked and advised its own ofcials not to fly with the airline.

The only comfort for the Berkleys was that on another flight, at another time, they could have lost two or even all three of their sons. Jean says of Matthew, two years younger than Alistair: “It’s ruined his life.”

The couple flew back to Britain within days of Lockerbie and youngest son James borrowed a cottage on Lindisfarne the family could withdraw to.

“I’d had the Christmas cake and pudding all ready made, so I brought them over with me, as well as the presents I’d got the boys,” said Jean. “I still had Alistair’s presents among them. It took a long time to absorb.”

The couple have used the compensation money that was part of the government-negotiated settlement with Libya to establish the Alistair Berkley Charitable Trust. It has funded a raft of projects in Uganda where the law lecturer had spent time.

Jean says the fight for the truth has kept them going. They want answers.

She adds that they did visit Lockerbie not long afterwards, to see where their son had died. But she is glad that they didn’t go to see his body, as they could have done.

“Dead people look different. I want to remember him as he was.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here