BACK from the dead and kicking ass again, 1970s die-hard rocker Wilko Johnson is back to his usual no nonsense, non-pc self, thank God!

Now recording and touring again, he told the packed Queen’s Hall auditorium: “Cancer was a pretty good career move! I’m doing some pretty big gigs and some of the festivals this summer – whichever way the wind blows, I go with it.”

Given 10 months at most to live in 2013, following a diagnosis of pancreatic cancer, by month 11 the one-time Dr Feelgood and Blockheads guitarist was busy recording an album with Roger Daltry.

The exchange at one of Wilko’s farewell gigs, with a music photographer-cum-oncologist called Charlie Chan, that he must have been misdiagnosed or he’d already be dead, is now legendary.

And the guy was right. A mammoth operation subsequently saw off a three kilogramme tumour, half of Wilko’s innards and a less deadly form of cancer, but not before he’d finished that album Going Back Home.

“Roger had approached me during an awards ceremony and said we should record together and when word got out about the cancer, he came back to me and said we must do that album. I said we’d better do it quick.

“By then, I was thinking ‘well, I’ve had a pretty good life, I’ve travelled the world and had my kicks and now I’m making a last record with Roger Daltry’.

“When it came out, it turned into the third best-selling album of 2014 and I was sitting there thinking ‘I was supposed to be dying’.”

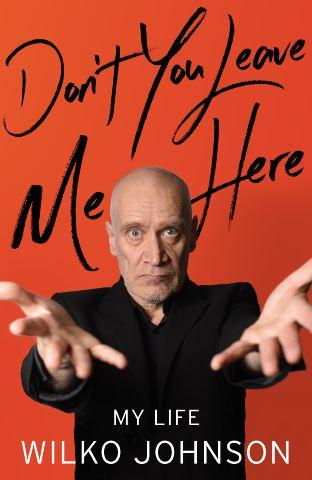

His Hexham fans laughed their socks off and applauded by turn as he was interviewed by BBC Radio Newcastle’s Doug Morris on Wednesday night, and then, this being a Hexham Book Festival event, snapped up dozens of copies of his autobiography Don’t You Leave Me Here.

A bird’s eye view of the grey and shining pates, in what must have been the longest book-signing queue ever seen in the Queen’s Hall, confirmed this was an adulation cemented long ago.

But this was, after all, the pub rocker who helped pave the way for punk. The purveyor of the mean guitar riff, the even meaner stare and the constipated duck walk, penned some of the early material that turned Dr Feelgood, in the words of The Stranglers’ Jean-Jacques Burnel, into the bridge between “the old times and the punk times”.

And like any rehydrated rocker, he’s got a damned good tale to tell.

Take the one about the irascible Ian Dury, for instance, and his penchant for picking a fight. Dury’s bristling exterior masked the fact he never believed anyone could just like him for himself.

“He always had to test people but, Christ, he could be offensive, particularly when he had a couple of drinks in him,” said Wilko.

“One night, we were staying in this posh hotel with the rest of the Blockheads when I got a phone call in my room to say Ian was losing it with an American in the bar.

“Anyway, I went along and this guy was seriously at the point of thumping Ian, so I got in between, separated them and made our apologies.

“Ian by this time was behind me, with another couple of our guys, one of them who looked just like me and the other a Rastafarian, and he was kicking off again, at someone else this time, so the three of us turned on him and started man-handling him out of the bar.

“I always wonder what it must have looked like to other guests, seeing two spivs and a Rasta dragging a cripple out of a bar.

“Ian wore calipers, of course, and we dropped him on his bed and took them off him, so he couldn’t walk. As we left his room, he was shouting ‘bastards, you’re all sacked!’”

Now 68, Wilko’s book begins at the beginning, with his childhood on Canvey Island in the Thames estuary.

His beloved wife of 40+ years, Irene, who lost her own battle with cancer in 2004, had supported him right from their earliest days together, as teenage sweethearts.

He’d craved the Fender Telecaster he’d spotted in a local shop, but the price tag of £107 – a small fortune in 1965 – was way beyond his means. However, when the price was reduced to £90, he’d gone for it and put down a deposit.

“In those days, you weren’t allowed to make any financial dealings under the age of 21 without parental permission and my mother wouldn’t have allowed me to have a credit arrangement,” he said.

“I asked if I could pay them in instalments and they said yes, so I used to go in and pay them out of my dinner money.

“They kept the guitar in the shop and each time I went in, they would allow me to sit and play it.

“It was taking ages though and by then, that particular guitar was very fashionable because Eric Clapton was playing one, so they weren’t very happy about it.

“It just happened that Irene had the exact amount I owed in her Post Office savings account and although her father wouldn’t have been happy about it at all, she got the money out.

“I’ve still got the guitar, but I haven’t got Irene any more.”

He left Canvey Island for an English degree at Newcastle University, where he chose all the medieval courses open to him, including a study of ancient Icelandic mythology.

“I was the only one who took that option,” he laughed, before reciting part of a “wonderful old story” – in an Icelandic tongue now dead to most.

Incidentally, he first visited Hexham when he was tasked with building a 10ft high crucifix for the university’s drama group, when it mounted a production in the Abbey.

“I felt like a medieval mason, I really felt part of that building, as I swung my hammer and ‘bang’, in went the next nail.”

After graduation, he briefly taught English, during which time the “long-haired hippy wearing a tank top” distinguished himself by sitting cross-legged on the teacher’s desk, looking for all the world like he was meditating – until a fateful meeting sent him ricocheting off on another orbit entirely.

He was just walking along on Canvey Island one day when he bumped into budding Dr Feelgood front man Lee Brilleaux.

“Lee was a very, very vivid personality,” said Wilko. “He was so intense and he had this great thing on stage – there was this tension and violence about him. He was a front man!”

But six years later, just as the band was getting gigs abroad, the tension between the guitarist with an amphetamine habit and the vocalist partial to his drink proved too much.

The band’s official website says Wilko left – he says he was kicked out.

Motorhead’s Lemmie said: “Speed freaks and drunks don’t get along!”

Whatever the truth of it, the pair never saw each other again and Brilleaux died of cancer in 1994 at the age of 41, two days after Kurt Kobain.

Wilko himself said he’d never felt more alive – elated, even – than he did during the year he thought he was dying.

The depression that had plagued him throughout his life had vanished as he savoured every last moment.

“You have this bubble around you and in many ways, it’s a marvellous feeling – you are standing apart from the world,” he said. It makes you think about what’s important, I learned a lot about life.

“But I’ve got my feet back on the ground now.

“ As I came back down to earth, I thought ‘here comes the misery again’. I felt myself getting lower and lower and thought ‘yes, I’m getting better’.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here