HE WAS born in a small village 10,000 feet up in the Himalayas, in the Nepalese province of Manang.

It was 1967 and just 200 people lived there. Many of them were, like his family, Tibetan refugees living a stone’s throw from the border with their real home.

His parents had five sons and so it was expected – it was the natural step – that at least one or two of them would be entered into a Buddhist monastery. It was an honour and a way of accumulating merit for a poor family.

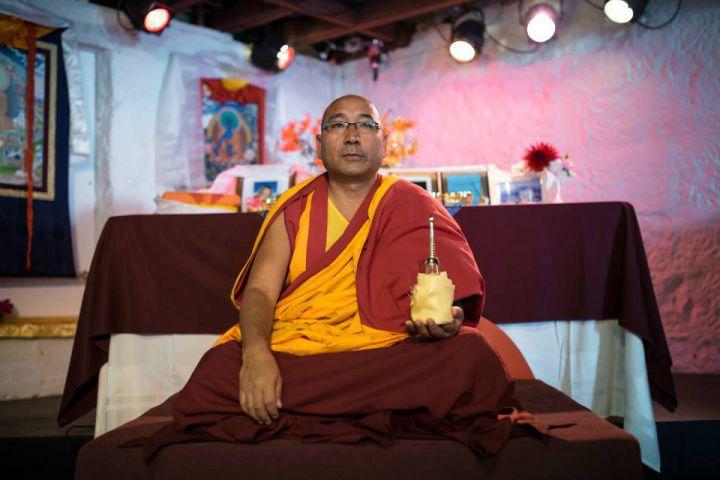

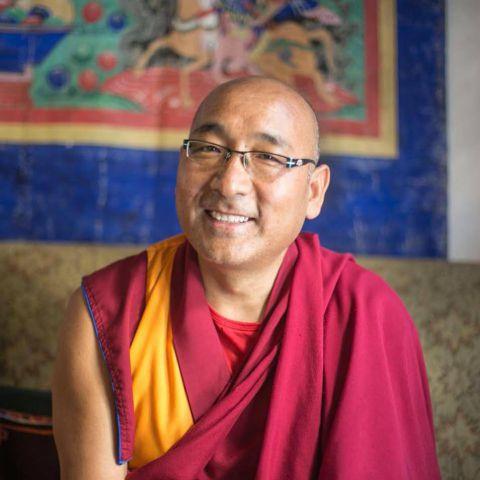

Sherab was nine years old when Lama Yeshe, one of the two renowned founders of the Kopan Monastery in Kathmandu, accepted him.

Years of study followed, much of it in India, until he’d earned the title of Geshe – attributed to the holders of degrees in Tibetan Buddhism – and attained the level that made him eminently qualified to return to his alma mater, the Kopan Monastery, as its headmaster, teaching the next generation.

He held that post for a few years, before deciding to relinquish it in favour of what he’s doing now. Travelling the world, spreading the word.

America, Canada, Mexico, Asia, Europe ... and his most recent visit, Greenhaugh and the Land of Joy Buddhist retreat tucked away in the rolling green hills of the North Tyne Valley.

He led a retreat there, teaching participants not only the practice of bodhicitta – in which the ultimate aim is to achieve enlightenment by replacing the sense of self with a sense of all sentient beings – but also how to achieve a therapeutic emptiness at the heart of daily life.

For ‘emptiness’ read a sense of inner peace that can help us all survive in a turbulent world, Geshe Sherab said during a public talk he gave at Hexham Community Centre.

His fusion of eastern philosophy and western culture, he feels sure, can help us all cope in these frenetic times.

“How to keep your minds peaceful despite the many difficult challenges surrounding us?” he began. “That’s a big job in times such as these.

“But it’s important to look at how we can keep our minds positive, hopeful and calm so that we are not overwhelmed and devastated by negativity.

“It’s not a simple job, but it is possible.”

Learning to meditate while focusing on improving our innate qualities of kindness and patience was the starting point.

The possessor of those traits in abundance could stand strong, like a mountain, in the face of any level of wind and rain.

“Like the mountain, you feel the rain and the winds and everything that’s happening around you – you feel the pain and suffering of others – but like the mountain, you are strong and unshakeable.

“A lot of time we underestimate the power of the mind, but its power is limitless.”

Another metaphor was the stillness in the deepest part of the ocean. There might be waves big and small on the surface, but down below, all was calm.

Achieve that and you not only dealt with the tribulations of daily life more effectively, but better contributed to the world at large.

The more we felt battered by the waves, the less we contributed to society. “It’s like a surgeon trying to operate,” he said. “If they are distressed, they can’t perform well.”

Remaining hopeful was at the very heart of his philosophy.

The monk, who lived and worked in the United States for many years, said the reason Donald Trump became president was because so many Americans had lost heart.

“Half of those eligible to vote didn’t do so – only 47 per cent voted in the election. So 53 per cent of 97m voters didn’t turn out, and the reason they didn’t vote is because they felt hopeless.

“They didn’t participate because they felt nothing would change and hopelessness turned them all into couch potatoes. They became indifferent.

“They sure regret that now!”

In difficult times, people had to remain open minded, trying hard to see the bigger picture. The opposite route was a downward spiral into gloom.

The world might seem like a more turbulent, unsafe place today, but to put it into perspective, the fluctuating stability of countries during the past 50 years just didn’t compare with the tragedy of the Second World War, or the suffering enduring during the Great Depression of the 1920s, or the horrors of the First World War before that.

“It’s not so bad today!” he smiled. “It’s all relative. It’s how you look at life.

“Some places might be a bit worse off, some a bit better off, but if you look at the bigger picture and look back through history, we aren’t in a bad shape.”

Taking the past century as an example, it might have been punctuated by those terrible events, but there had also been real, life-enhancing progress.

Slavery had been abolished, women had gained suffrage, the rights of animals had been recognised too, and living standards had been raised in most parts of the world.

The thing was, though, the constant flow of news, brought to us from all over the world by an intrusive media, bombarded us with a sense of war, strife and stress on an almost hourly basis.

It gave the impression the world was a much worse place to live in than, say, 100 years ago. But as the centenaries of the battles of the ‘Great War’ roll today, just think what a state Europe was in back then!

“Sometimes there’s a bump in the road, but no matter how big the bump, humans have the ability to overcome them because they created them,” said Geshe Sherab.

“It’s all about directing human minds in the right direction, so that they can fix problems.

“And if you keep looking at the bigger picture, there is always hope.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here