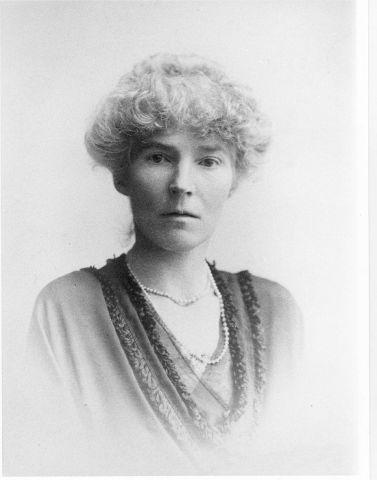

TODAY it’s hard to understand how a woman such as Gertrude Bell, the pioneering spirit who loomed large in the early 20th century politics of what is now the Middle East, did not believe women should have the vote.

Indeed, she felt so strongly about it that in 1909, she became secretary of the northern branch of the Anti-Suffrage league.

Given her history, you would surely have expected otherwise from this fierce intellect, with her thirst for travel and her high-flying career.

She was the first woman to graduate in modern history from Oxford with a first class honours degree, something she achieved in just two years.

Bell was also the youngest to do so, having enrolled at the age of 17, and simply attending university in the 1880s, was a test of mettle for the fairer sex.

Professor of history at Newcastle University, Helen Berry, has long been fascinated with the society, culture and economics of the times.

In a chapter she contributed to the definitive biography The Extraordinary Gertrude Bell, Prof. Berry said: “Life for women was not easy at Oxford: they had to remain silent in lectures and could not interact freely with professors or male classmates.

“In some classes, Gertrude and the other women even had to sit with their backs to the lecturer.”

Of aristocratic stock, she was the daughter of Sir Hugh Bell and granddaughter of ‘ironmaster’ Sir Isaac Lowthian Bell, an industrialist and Liberal MP (during Disraeli’s tenure) who was as famous in his day as his contemporary, Isambard Kingdom Brunel.

Incidentally, she was also half-sister of Molly Trevelyan, chatelaine of Wallington Hall. Molly’s youngest daughter, Patricia, who died five years ago at the age of 98, described Bell fondly as ‘my fearsome aunt’.

Both Bell’s father and grandfather served in a succession of Government posts, so she grew up with politics. Added to that, her uncle, Sir Frank Lascelles, was British ambassador to Tehran, in what was then Persia.

In 1892, she made her first trip to Persia, to visit Uncle Frank. And then for a decade she just kept on travelling ... through Europe, the Ottoman lands and, most of all, Arabia.

Along the way she mastered six languages (Arabic, Persian, French, German, Italian and Turkish), became a well-respected archaeologist and established a mean reputation as a mountaineer.

Everywhere she went, she milked her connections for all they were worth, said Dr Mark Jackson, senior lecturer in archaeology, manager of Newcastle University’s Gertrude Bell Archive and co-editor of The Extraordinary Gertrude Bell.

“She worked the system,” he said. “Whenever she arrived somewhere, she knew the way to quickly establish her status was by only dealing with the people at the top.

“If she wanted to get something done that came under the auspices of the Viceroy of India, then she went to speak to him in person.

“If she wanted to travel through a particular part of the Ottoman world, she went to the most high-ranking official to gain the protection of that person – in Constantinople, she had the protection of the Grand Visier himself.”

Having criss-crossed Arabia as an archaeologist, mapping historic ruins as she went, at the outbreak of the First World War she requested a posting to the Middle East.

Recognising her rare knowledge and insight, British Intelligence eventually recruited her to guide soldiers through the desert landscape. Her network of contacts within local tribes expanded exponentially as a result.

In 1915, she was summed to Cairo to join the fledgling Arab Bureau, along with one T.E. Lawrence. The doughty pair had a lot in common: that First Class Oxford degree in modern history, the fluency in Arabic, the extensive Arabian travels and, crucially, the ties with local tribes.

Director David Lean notoriously wrote Bell out of history in his film Lawrence of Arabia, but in reality, she was as instrumental as her male counterpart in recruiting the Arab tribes to help drive the Turks and their Ottoman Empire out of the region.

She wrote Self-Determination in Mesopotamia, a paper that earned her a seat at the 1919 Peace Conference in Paris. She also attended the 1921 Conference in Cairo with Lawrence and Winston Churchill, then colonial secretary, to help define the boundaries of Iraq.

The coup de grace of the desert duo was putting forward the name of Faisal bin Hussein for the newly-cast throne. Faisal the First was duly installed and henceforward Bell, the king-maker, was frequently addressed as khutan – ‘queen’ in Persian – by the grateful people of Mesopotamia.

There was nothing this woman couldn’t do, it seems – except marry the man of her choosing. For when, at the age of 27, she fell for British embassy official Henry Cadogan, her father said no.

This dutiful daughter of Victorian England accepted his decision, and there we have it, the first overt sign that within this apparently modern free-thinker lay the soul of a traditionalist.

Or, at least, she believed everyone else should conform to the status quo. That didn’t apply to herself, of course, said Dr Jackson. “As far as she was concerned, I think she felt you worked within the system – you didn’t undermine it or overthrow it.

“She was particularly good at having agency within the existing structures, because of her family’s wealth and connections, so she could already achieve what she wanted to.

“In other words, she didn’t need women to be able to flex the power of the vote – she had all the power and influence she herself needed.’

This ‘I’m alright, Jack!’ attitude was matched by a concern that people who didn’t have access to power, well, shouldn’t.

He said: “I think she felt that the people who make decisions about making decisions should be qualified to do so, and people who didn’t fully understand – who lacked the right knowledge and education – would vote in an ill-informed manner.”

As for the Suffragettes themselves, opinion is divided today over whether the increasingly radical lead provided by Emmeline Pankhurst actually helped or hindered the cause, but it’s not hard to guess what Bell’s view would have been. Prof. Berry said: “There was a distaste amongst the establishment that women were behaving very badly and inappropriately. It had moved into hunger strikes, so I think Gertrude’s response was very much of her class.

“She identified very strongly with people in authority, who worried that this was going to lead to a breakdown in society.

“It was important to maintain stability in the Empire and women should stick to their correct role,” he said.

“But she regarded herself as completely exceptional to that.”

* The Extraordinary Gertrude Bell, edited by Mark Jackson and Andrew Parkin, is available from Newcastle City Library

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here