IT’S a question generations of school children and visitors have asked and a good one at that.

Where did all the building blocks of Hadrian’s Wall go?

It once cut a mighty 86-mile long swathe across our landscape, looming large at 15 feet tall and nine feet wide.

Years of Roman-inspired toil had fashioned thousands of tonnes of neatly-cut, uniform sandstones that together made up the Wall’s length – stones that are so obviously missing from its mouldering ruins today.

As Greenhead resident Wendy Bond, an active member of many a community group and endeavour, says: “Whether we live in an estate in the city of Newcastle, in one of the small villages in Northumberland or Cumbria, or on one of the isolated farms balanced high above the valleys, we know our Wall’s surfaces, its ups and downs, its associated earthworks.

“However, for many of the thousands of visitors to our stretch of Hadrian’s great works delineating the Frontiers of the Empire – all now designated as a World Heritage Site – the Wall can be hard to find, hard to distinguish and occasionally rather disappointing.”

While setting out to answer the question in the booklet she’s just written, Hadrian’s Wall: Where have all the stones gone?, Wendy begins at the beginning – and the skill of those who constructed this defence of Hadrian’s most northerly frontier in the first place.

It has been calculated that around two million cubic metres of stone was used, and the locations of some of the quarries the Romans drew it from are known. Some of the men at the rock face carved their names for posterity.

Irregular blocks of sandstone were usually dressed to just about the same size and shape at the quarry – ideal for men to both carry and fit together as facing stones on both sides of the Wall – and then glued together using lime mortar.

That was made by burning the local limestone in a manner described by Pliny the Elder in Roman times and still used in Romania today.

Wendy says in her booklet: “As each unit of soldiers completed another 45-metre stretch of the Wall, they carved their details on to a facing stone. We still have about 150 of these, mostly now in museums to preserve them.

“These help scholars to build up a picture of how the work progressed and who was involved.”

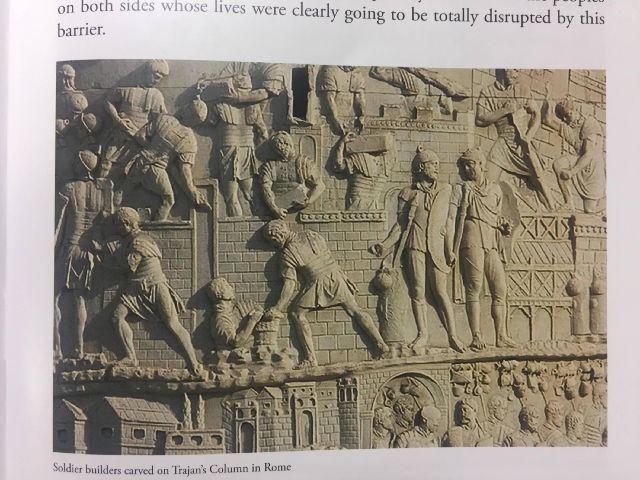

It was the Roman legionaries who actually constructed the Wall – each one had to be as proficient at building as fighting. They also had to work fast and in harmony with dozens of people around them, as scenes depicted on Trajan’s Column in Rome illustrate.

In chapter three, Wendy looks at who worked on the Wall after the Romans left. “The Anglo-Saxons and Vikings who raided and infiltrated the Wall country over the next centuries were devotees of wood rather than stone, on the whole,” she says.

“The Normans didn’t arrive to settle as far north as the Wall until the reign of Henry II (1133-89) ... so this next group of stone-builders didn’t arrive on the Wall scene until well into the 12th century AD.

“This explains why there is nothing in the Domesday Book about the Wall.”

The Normans were renowned for their castle building skills, so what happened next was entirely predictable.

Hadrian’s Wall became something of a builders’ merchant, top supplier of dressed stone!

“The first castle built from that handy pile of nicely shaped stones may have been Triermain, erected by Hubert de Vaux, who obtained his barony near Gilsland from Henry in 1157,” writes Wendy.

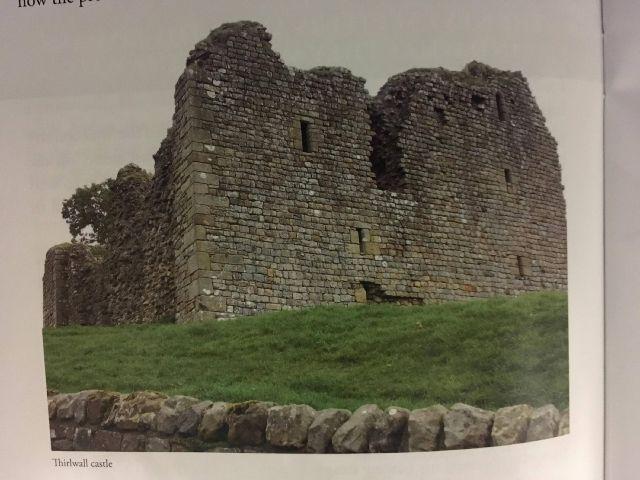

Similarly, it is recorded that in 1330, John de Thirlwall was granted permission to build himself a four-storey high fortified house, complete with a crenelated tower and three-metre thick walls.

One look at Thirlwall Castle today and you know it has been built out of Roman-dressed stones.

Wendy said: “The other effect of the Normans was to recycle the Wall for churches, from the tiny, humble 12th century church at Upper Denton to the mighty Lanercost Priory, founded in 1166.

“Both contain a considerable amount of the stone from the Wall and from the fort at Birdoswald.”

Eclectic and meandering in its approach, Wendy paints a fuller picture of the Wall and this remote northern frontier.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here