LOOKING at the photographs unearthed for a forthcoming First World War history exhibition about the Territorials who came to Tynedale and Redesdale, it’s hard not to contemplate the unseen horrors that lay in wait for these men.

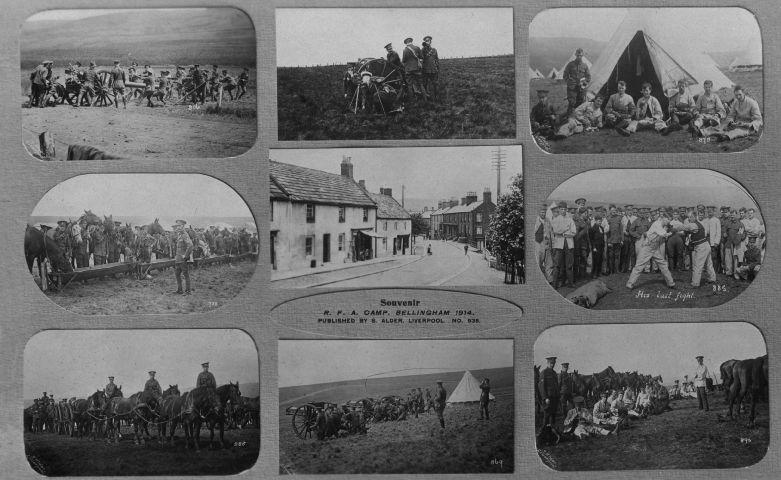

Faded pictures portray them proudly sitting on horseback or tucking into their rations outside white bell tents and drinking mugs of tea with their comrades.

Indeed, the training grounds that these hundreds of reserve soldiers came to from all points of the compass, perhaps just weeks before being posted to Passchendaele, Ypres or some other version of hell, seem akin to a pastoral idyll in comparison.

The touring exhibition, which opens at Bellingham Heritage Centre next month, is the result of a £9,900 Heritage Lottery Funded research project by historians David Walmsley and Stan Owen.

Accompanying it, is a fascinating 20-page free booklet, Territorial Training: The Redesdale and Hareshaw Army Camps and an online educational resource for schools.

David, a former teacher, who went on to become education manager for English Heritage in the North-East, before going freelance, said it had been like putting together a jigsaw that had several pieces missing.

“It started off by us discovering a few old pictures in the centre’s archive that we didn’t have any information about,” he said.

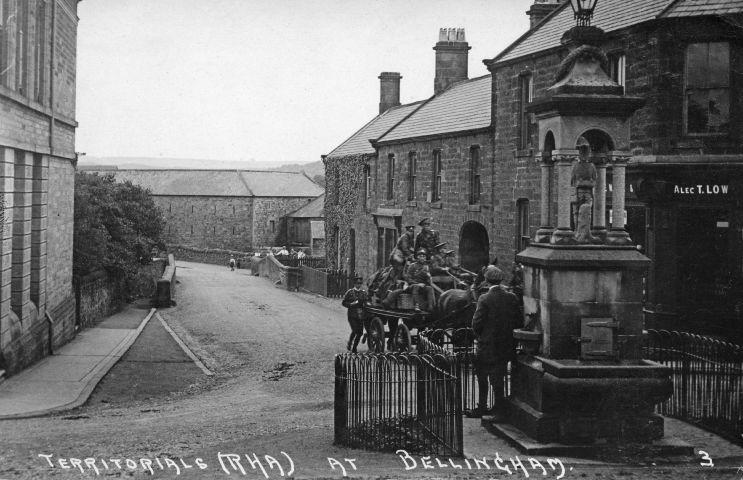

One of those in the booklet shows a group of soldiers on top of a horse-drawn cart. Printed at the base of the photograph are the words: ‘Territorials (RHA) at Bellingham.’

RHA stands for Royal Horse Artillery and it set David and Stan off on an archival adventure to try and find out more about what on earth they were doing there.

Stan, a former classics teacher, is an authority on the work of early photographer, Walter Percy Collier, whose collection of images can be seen at Bellingham Heritage Centre alongside a recreation of his shop. Stan researched the photographic angle whilst David travelled to London’s Imperial War Museum and the Royal Artillery Museum at Woolwich to pore over old maps and newspaper articles.

“Some questions we’ve answered and some we haven’t, but that’s the nature of research,” David said.

Local legend has it that it was Sir Winston Churchill himself who first suggested using the moorland for military training. “He was staying with Lord Redesdale on a shooting holiday at Birdhopecraig Hall but they mustn’t have had a good day as he reportedly said that the moorland would be better used for shooting much bigger guns!” David said.

The story goes that when the Government was looking for land on which to build a training camp, in the aftermath of the Boer War, somebody reminded them of Churchill’s observation.

Lord Redesdale supplied some of his estate along with other landowners and the Redesdale training camp was opened in 1911 amidst protest from some quarters that shepherds would lose their livelihoods.

“That camp was the forerunner of the Otterburn ranges,” David said. “But not long afterwards, they realised that they needed an additional camp for extra capacity so they opened one at Hareshaw Common, just outside Bellingham and soldiers from the Territorials would come there for a week and then march to Redesdale for the second week.

“They came from all over the country, including Manchester, London and Edinburgh, travelling by special trains to West Woodburn or Bellingham stations.”

A report from The Manchester Courier of July 1914 records various trains carrying the 2nd East Lancashire Brigade RFA reaching Bellingham at 4.30; 5.30; 6.30 and 7.30 in the morning.

They then had to ride or march the two and a half miles to the Common, much of it up hill.

“The brigade were fortunate to have settled comfortably into camp before rain came down in a steady downpour, which continued for the rest of the day,” wrote the reporter.

Aside from the sometimes inclement weather, camp life appears to have been a welcome break for some.

David said, “You have to bear in mind that quite a few of these men will have come from towns and worked in factories and mines so for some, two weeks of training in this vast countryside was almost like a holiday.”

That would certainly have been true for those who came in the early years of the camps prior to the immediate threat of war. The Territorial Force had been set up as a ‘standby’ army in 1908 and the camps up here were designed to equip them with all the fighting skills necessary for the modern artilleryman.

The thing that most amazed David and Stan during their research was the sheer scale of the operation.

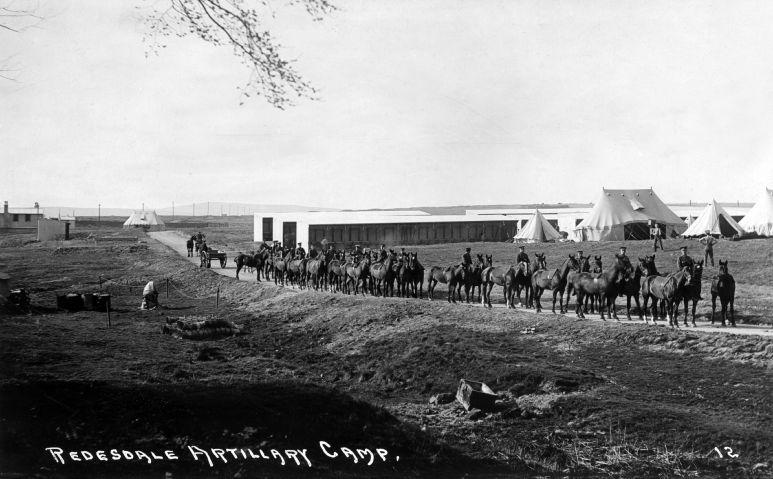

“We don’t have accurate numbers because the (Redesdale) Territorial training camp didn’t keep any records,” David said. “But you can see the enormity of it in the photographs. In fact Redesdale camp was referred to as the ‘Northern Aldershot’ because it became so big.

“What people don’t realise is that because they were using large guns they needed horses to pull the guns and ammunition carts on to the firing ranges.

“The Army used local men to build rows and rows of stables for 600 horses made of wood and corrugated iron and built on concrete bases.”

Whilst the everyday soldiers would sleep in bell tents, senior officers of the regular army lived in relative luxury in Birdhopecraig Hall which was destroyed by fire in 1957.

Local volunteers at the Bellingham Heritage Centre helped David and Stan piece together their jigsaw.

“Sue Underwood, one of the supporters, took out a subscription with the newspaper library of the British Library online. And she uncovered a newspaper article about the training and the competitions that was fascinating because that really started to show what they did,” David said.

“They had these inter-brigade competitions to see who were the quickest or best at firing guns, or who were the best teams at driving horses that pulled the guns and wagons.”

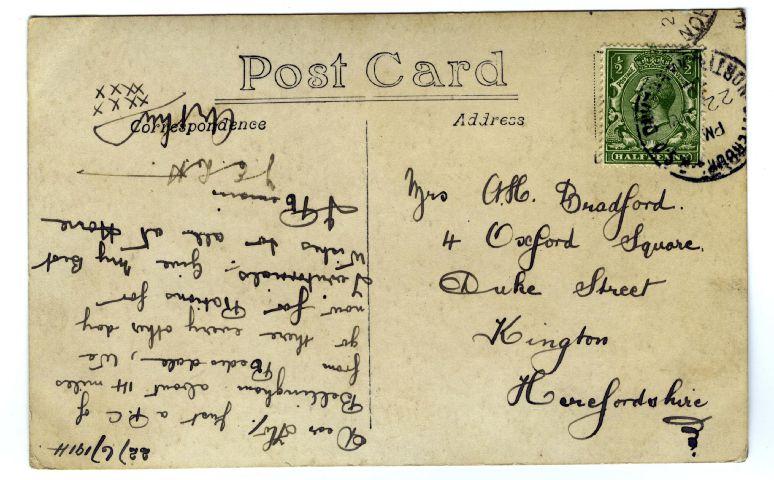

During their down time they often wrote postcards, produced by local photographers, and some of these are featured in the booklet.

One, sent by one Arthur Bradford, a member of the Army Service Corps at Redesdale Camp, to his wife Flo in Herefordshire during the summer of 1914, says: “Just a P.C (postcard) of Bellingham about 14 miles from Redesdale. We go there every other day now for rations for Territorials. Give my best wishes to all at home.”

You find yourself wondering what happened to Arthur in the turbulent years that followed, as you do about all the faces in these pages.

It’s one of the unanswered questions.

As David said: “Quite a few people who I have shown the booklet to often ask how many of these men would have come back and what they could have experienced in three, four or five month’s time.

“We see them marching away together to Bellingham Station knowing that they will eventually end up at the front without any clue about what they were going to face and the ordeals they would have to endure.

“It’s all very well seeing these carefully composed photographs in and around Redesdale and Bellingham, taken in good weather but we know that on the front they experienced some of the worst winters – wet and cold – where fallen men literally disappeared into the mud. That’s not conveyed by these shots of brigades training in such tranquil countryside.”

The particular value in this booklet, which is deliberately written in a very accessible form so that children can read it or have it read to them, is that it’s a record of two camps that have all but disappeared from the landscape.

Hareshaw Camp seems to have closed for good upon the outbreak of war. However, Redesdale became an important site for the training of infantry soldiers and aerial photographs still show the practice trenches they dug there. Its camp and firing range grew and grew as the Army bought more land. The stables were demolished as tracked vehicles for gun transportation replaced horses. Redesdale was swallowed up by what became Otterburn Army Training Estate, the UK’s second biggest firing range which still trains more than 30,000 soliders from all over Europe every year.

* Free copies of the booklet can be collected or posted out from Bellingham Heritage Centre. Call 01434 220050 or email info@bellingham-heritagecentre.org.uk

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here