THE good burghers of 1820s Hexham were outraged!

Drive a road across their beloved Seal parkland?

Only the rather wayward Thomas Wentworth Blackett would have agreed to that.

To give him his due, he was more commercially minded than his father and more aware of the needs of the traders of the time.

But as Lord Allendale says of his predecessor: “He was a bit of a reprobate – a wild card, to put it mildly – but his mother put a rocket under him on that occasion.”

On Monday, Lord Allendale joined the members of the steering group tasked with marking the 150th anniversary this year of the building of Beaumont Street.

The official period of celebration will kick off on April 23, when Hexham Spring Fair and a St George’s Day parade will provide the perfect platform to highlight all that is best about the architectural treasure and trading lifeline.

But if it hadn’t been for Thomas Wentworth Blackett’s mother, Diana, the town might have had a different complexion altogether.

Local historian Mark Benjamin set the scene.

“The impetus for Beaumont Street came from the modern age of transport and the evolution of long-distance commercial travel that had begun with the turnpike, or toll, roads.

“The great age of the turnpike roads, which arguably represented the first serious major road building programme since the Romans, was in the 1700s and there were three running through Hexham.”

They ran to the east, west and north, this last one the Corn Road, used to transport grain to the commercial shipping fleet at Amble.

The one that came into Hexham from Haydon Bridge, the Glenwhelt Turnpike Road, followed what is now roughly the route of West Road and Hencotes.

In 1771, the Glenwhelt was extended to provide an improved link with the growing industrial powerhouse that was Newcastle – but at a cost to Hexham.

“The lead trade was booming at the time and Newcastle was really coming into its own as an industrial centre, so that new road made sense,” said Mark.

“But the problem was the trade route then bypassed Hexham and people needed to look at creating a link to the town centre and the market place at its heart.”

In 1820, a proposal was made for a new turnpike road between Hexham and Haydon Bridge, but when traders objected to the fact the plan didn’t contain a spur into the market place, an alternative route was put forward – straight across the Seal (as it was traditionally spelled).

As the scion of the Lords of the Manor, the hapless Thomas agreed, and caused a public outcry.

By then, townsfolk had for 70 years enjoyed the right to promenade on the Seal, ever since Sir Walter Calverley-Blackett had opened it to the public at the height of the era of Capability Brown and the great parks.

On September 27, 1823, having got wind of Diana Blackett’s scheduled meeting with a surveyor to discuss the two possible routes for the new turnpike road, members of the public turned out in force to beg her to protect the park.

It made sense to take the route past the front of Temperley House instead, they argued, the grain merchant’s building that today houses the Abbey Dental Practice and the Granary apartment block above.

(Temperley’s actually existed as a merchant of corn and animal feed well into the 1980s.)

In one of Hexham Local History Society’s wonderful books, it is recorded that Mrs Blackett ‘was pleased to express herself to the following effect: “Gentlemen, I have examined the different lines of the intended new road and am fully of the opinion that the Temperley line is decidedly the best.

“I doubt not that they (the commissioners) obtained my son’s consent to the line passing through the Seal by representing to him that it was for the general good.

“But though he has the rents and proceeds of the property in this neighbourhood, yet I am still Lady of the Manor and no power on earth shall induce Colonel Beaumont and myself to do anything to deprive the inhabitants of Hexham of the comforts and privileges they have so long enjoyed in the Seal.

“Gentlemen, I thank you for your kindness and wish you all good morning.”

‘She then retired to her carriage, followed by the good wishes of all present, and the bells rang many a merry peal throughout the day.’

The need for a link to the market place remained a pressing one, though nothing was to happen for another three decades.

By the mid 1800s, Hexham was not only a centre for local and regional farm trade, but when it came to the growing demand for Hexham Tans – the finest of leather gloves – it was a centre for national trade too.

The leather makers in the Gilesgate/Cockshaw area were producing 23,000 pairs of gloves a year and not only did they need to get the gloves out, they needed to get the staples of their trade in.

Mark said: “This being Hexham, nothing much happens for another 30-odd years after the failed Seal bid, but in 1856, there is another attempt when the next generation of the Beaumonts – Wentworth Blackett Beaumont – buys the Abbey grounds.

“This is the time of Victorian reform, burgeoning industry and a general atmosphere of zeal.

“But Hexham has slums and cholera, so when a report is produced that basically describes Hexham as a filthy pit badly in need of reform, as Lord of the Manor, Wentworth Beaumont felt a sense of responsibility and the need to act.”

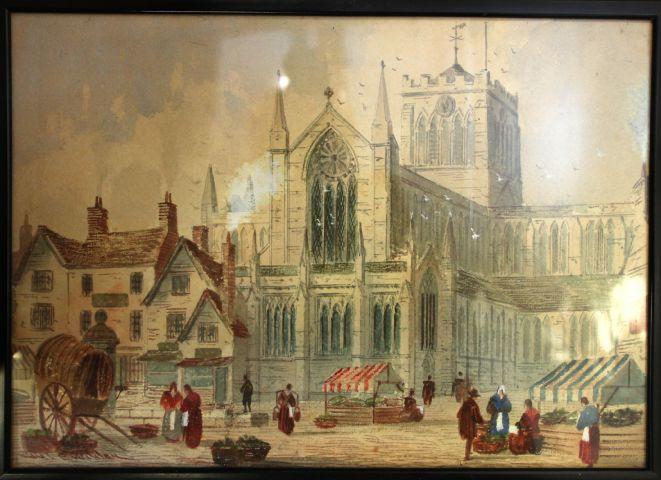

He duly set about consulting on plans to clear the decrepit end of the market place, comprising the derelict Lady Chapel element of Hexham Abbey and the old tenement buildings resting against its medieval boundary wall.

“At the same time, you’ve got the National Farmers’ Union saying their trade is thriving and they want a corn exchange on any road that might be developed into the market place,” said Mark.

“Basically, it was a case of ‘we’ve heard you’re contemplating some changes – any chance of a corn exchange?’”

The civic-minded Wentworth listened to them, but it isn’t until 1863 that he finally said in a public missive that ‘some day he hoped there would be a road to the market place’.

Undeterred by this vagueness, a group of leading farmers went ahead and instituted the Hexham Corn Exchange Company, and it was but a matter of time before they were inviting the worthy Wentworth back, this time to lay the foundation stone for the building that would for decades be the Corn Exchange and latterly, the Queen’s Hall.

By 1866, the farmers had both a vibrant trade centre, the envy of other industries, and a gleaming new street that in time would prove to be the acme of Victorian design.

In February, 1867, it was baptised Beaumont Street.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here