NENTHEAD is about to celebrate its part in an international story that counts Napoleon, Esperanto aficionado Dr Wilhelm Molly and a legion of Belgian, German and Italian miners among its cast of characters.

Over the weekend of August 6 and 7, the village will play host to several dozen European visitors gathering to mark the 120th anniversary of the arrival of the Vieille Montagne mining company in the North Pennines.

While the Saturday will be for the boffins interested in the finer points of the zinc and lead mining operations that defined the valley for half a century, the Sunday will be a fun-packed gala day for all the family.

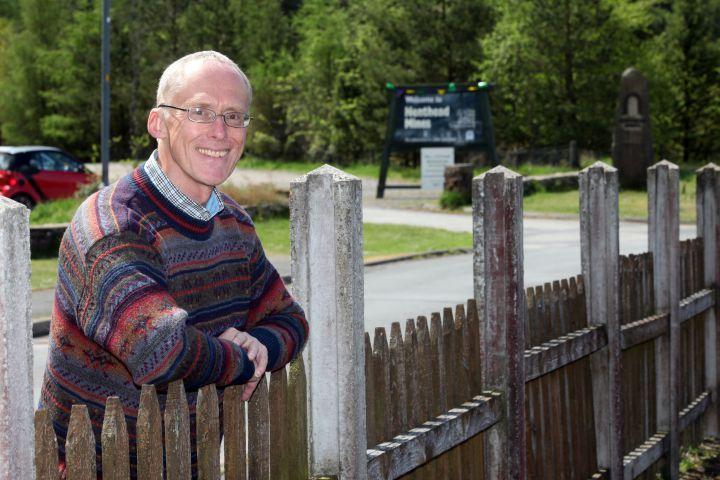

Eagle-eyed local historian Alastair Robertson instigated the event after spotting the anniversary potential while researching the history of the building that was once the company’s headquarters.

Thought to be structurally unique in Britain, the building is currently home to the Wright Brothers coach business, but it is on its last legs.

Brothers Ian and Gary are now preparing to replace it with a modern, fit-for-purpose garage and as part of the planning process, asked Alastair to carry out the level three historic assessment needed.

He was amazed by what he found. “Vieille Montagne has got a fantastic history!” he said.

“It began in Kelmis, which is now in Belgium, but for about 100 years the area had its own independent status – it belonged to no country – because of the value placed on the Vieille Montagne mine.”

The seeds for the company were sown in 1810, when Napoleon signed its concession for the extraction of zinc.

When Napoleon and his empire fell, the Congress of Vienna of 1814-15 redrew the map of Europe with the aim of creating a sustainable balance of power.

The border between Prussia and the newly-founded state of the Netherlands ran smoothly until it hit the district of Moresnet, location of the lucrative zinc spar mine named Altenberg by the Germans and Vieille Montagne by the French. Both countries wanted it.

A compromise was achieved by dividing the district into three, whereby each country gained a paltry village, but the land inhabited by the mine was declared neutral territory, pending further negotiations.

Barred from having a military presence in Neutral Moresnet, the two countries had to make do with a joint administration, and so things remained for the next 103 years.

Belgium gained its independence from the Netherlands in 1830 and took with it the interest in Neutral Moresnet, but by 1885 the mine had given of its last and the whole raison d’être for the department’s neutrality was gone.

Dr Wilhelm Molly, the mine’s chief medical officer, first put his head above the parapet when, as a keen philatelist and an avid supporter of its neutrality, he attempted to launch an independent Moresnet postal service, complete with its own stamps. The Belgians were having none of it, though!

An attempt to establish a casino and turn the department into a mecca for gamblers after Belgium closed all its own casinos was similarly thwarted.

But it was Dr Molly’s proposal, in 1908, to turn Neutral Moresnet into the world’s first Esperanto-speaking state – renaming it Amikejo, meaning ‘a place of friendship’, in the process – that brought him to international attention.

A scattering of supportive residents duly learned Esperanto, a rally was held in Kelmis and the subsequent World Congress of Esperanto, held in Dresden, even declared Neutral Moresnet the world capital of the Esperanto community.

Sadly, as with each of Dr Molly’s ventures, the scheme crashed and burned and Belgium, having run out of patience, simply annexed Moresnet during the First World War.

Luckily, the company the good doctor worked for was otherwise hale, hearty and thriving.

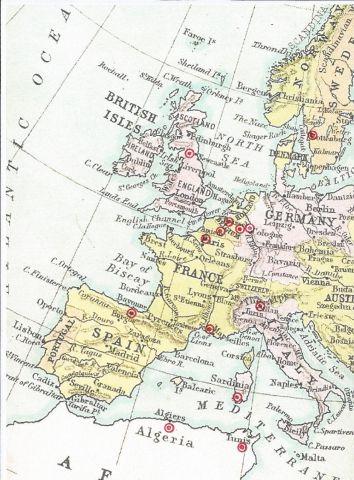

By the turn of the 20th century, Vieille Montagne had 41 mines and processing centres across Europe and North Africa.

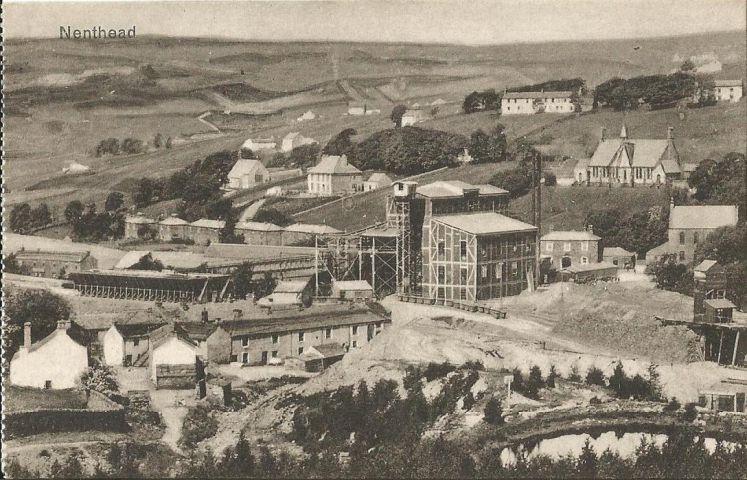

It had taken over the mine in Nenthead, and another one near Allendale, in 1896 and so productive were they that within a very short time, they were responsible for 60 per cent of Britain’s zinc output.

The zinc and lead was sorted, crushed and cleaned at Rampgill Mill in Nenthead and then transported by road, rail and sea to the parent plant in Belgium. That was the pattern for its mines worldwide.

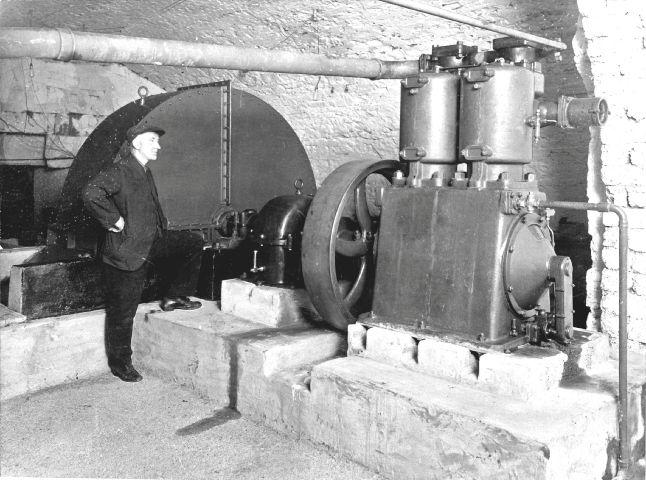

On the website he has established at vieillemontagnehistory.com, Alastair wrote: “The establishment of the Vieille Montagne Company at Nenthead was the start of an era of new technology, when previous methods and techniques were replaced by a new dynamism backed by huge financial investment.

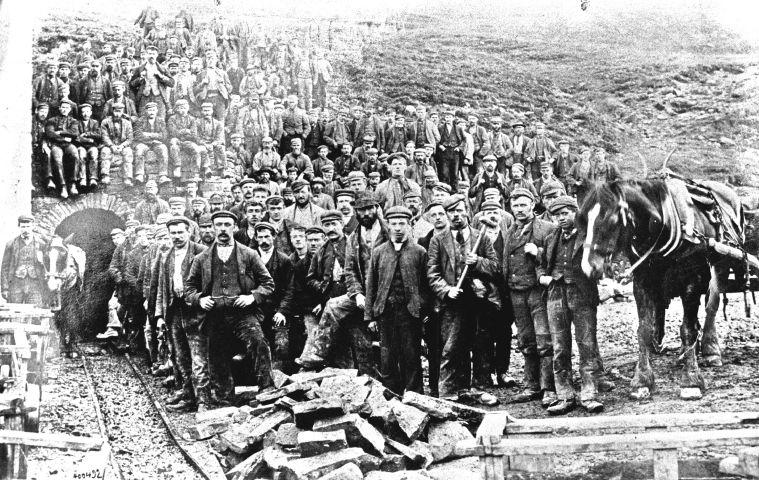

“VM invested many hundreds of thousands of pounds in the area. It was at the forefront of mining and ore processing technology in Britain and Europe, attracting visitors to the village to view its plant.

“It employed hundreds of men of several nationalities – mainly Belgian, German and Italian – and the local economy depended on its success.”

The company traded through the two world wars and the economic depression in between, but after riding the rollercoaster of fluctuating demand for 53 years in Nenthead, the company finally ran out of steam.

In 1949, it sold its leases, plant and equipment, and went home.

Alastair points out that while the London Lead Company is still revered and written about today thanks to the patrician ethos that shaped the model village of Nenthead during the 1800s, the public at large knows little or nothing about the Vieille Montagne Zinc Company.

The anniversary weekend and website are his first steps towards redressing the balance.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here