FIRST off, your heart goes out to poor Elizabeth Ord, although financially poor she was not.

Indeed, such was the wealth that surrounded the illegitimate daughter of Sir William Blackett that when her father died, she was sort of ‘handed on’ in his will.

Blackett’s then rightful heir, his nephew Walter Calverley, would only inherit the family’s lead mines, smelting mills and estates in Northumberland and Durham if he married Elizabeth within a year of his death, he stipulated.

That wedding duly took place in August 1729 in Newcastle.

Calverley also adopted the Blackett surname in compliance with his uncle’s wishes.

In an article entitled Elizabeth Ord: A Woman in the 18th Century, the author Ian Forbes says his aim was to draw out of the shadows this living, breathing person who was used ‘merely as a convenience to allow the continuity of the male line of Blacketts’.

Ironically, the only reason we know anything about her at all today is because of the legal manoeuvring of her covetous relatives.

They were a couple who depended on their guardianship of her for their own annual income.

Those skirmishes ended up in the court of Chancery, where a judge decided what was best for the defenceless young woman whose mother, also called Elizabeth, died when she was just one.

While William’s family seat was Wallington Hall and Elizabeth, the mother, hailed from the village of Ord in north Northumberland, William chose to live in London.

The pair had been sweethearts since their childhoods in Northumberland.

But although they lived together as man and wife in London, William made it clear that, for some reason, he had no intention of marrying the mother of his two children (their son William died at the age of six).

So fast forward to William Blackett’s death in 1728 and we find his 16-year-old daughter effectively alone, in an epoque unforgiving of illegitimacy.

How did Elizabeth fare? Was her marriage to Walter Calverley a ‘happy ever after’ affair?

And how did Wallington creep back into the story? Ah well, you know what to do if you want the answers!

Within what is the 28th edition of the Hexham Historian, you will also find the story of another family, this time round the members of which will be within the living memories of an older Newbrough resident.

The M. Charlton & Sons bus company plied the highways and byways of Tynedale for decades.

The son who led it during its heyday in the 1950s, Jack Charlton, only died in 2005, at the age of 94.

The company was started by Matthew Scott Charlton when he returned from the trenches of the First World War.

He was suffering from the terrible effects of chlorine gas poisoning.

Having been advised by medics not to return to the family joinery business and to find outdoor employment instead, he put his war pension into a small three-wheeled truck to provide cartage to and from the then Newbrough railway station.

He was 41 and had a wife, six sons and a daughter to support - he had to make a go of it!

And, indeed, he did.

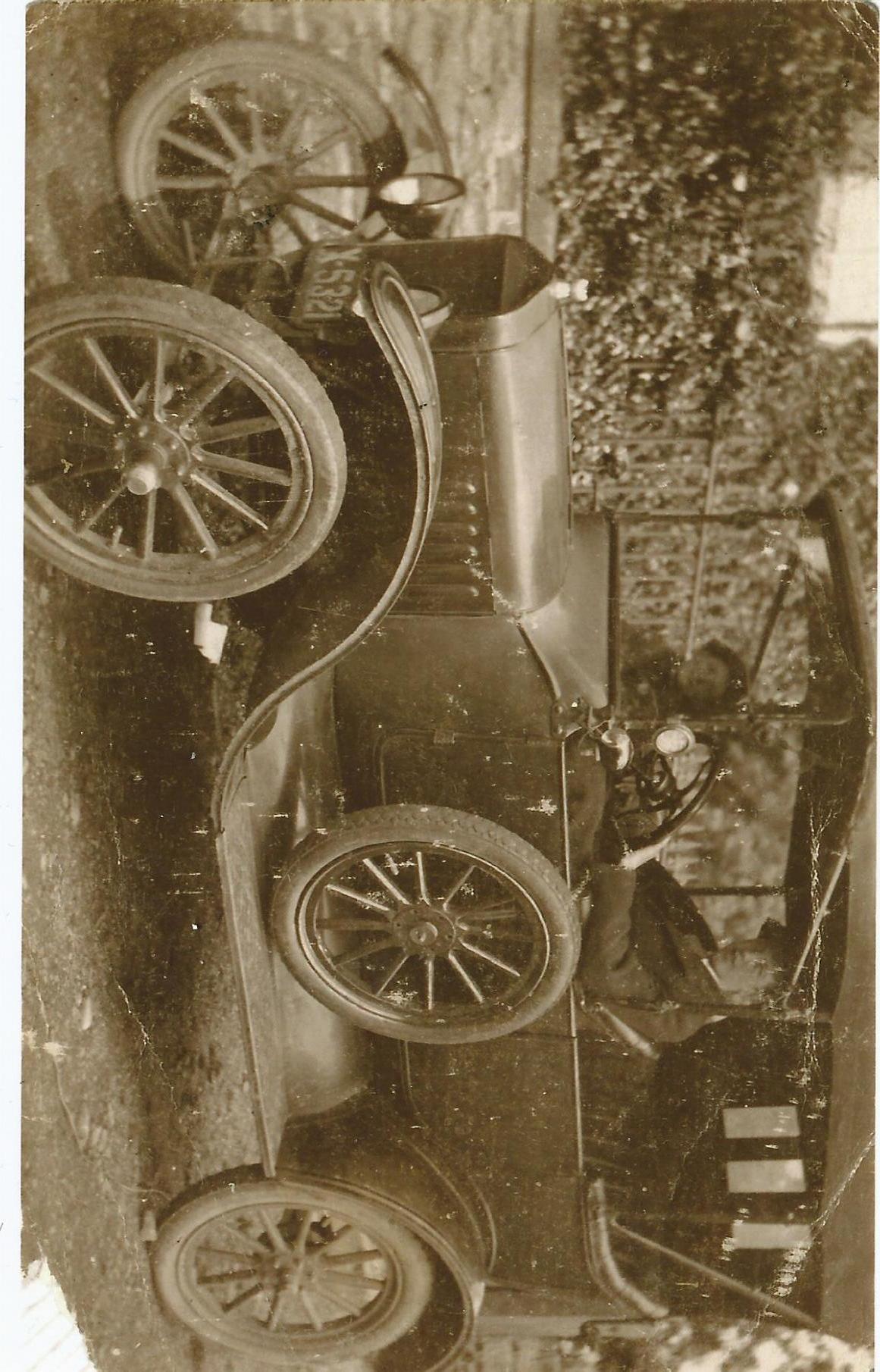

The service was so popular it wasn’t long before he’d extended it to Hexham railway station and bought a Model T Ford, so he could transport people as well as parcels.

At that time his eldest son, Tom, was serving an apprenticeship to be a mechanic with the Hexham Motor Company.

As soon as Tom had completed his time there, he joined his father and became responsible for driving the Model T.

As each son in turn turned 17, Matthew bought him a vehicle. Jack, his fourth son, said his first vehicle had been a Ford T wagon with solid rear tyres and no cab or side doors.

His father had rescued it from a farmyard for the princely sum of £10.

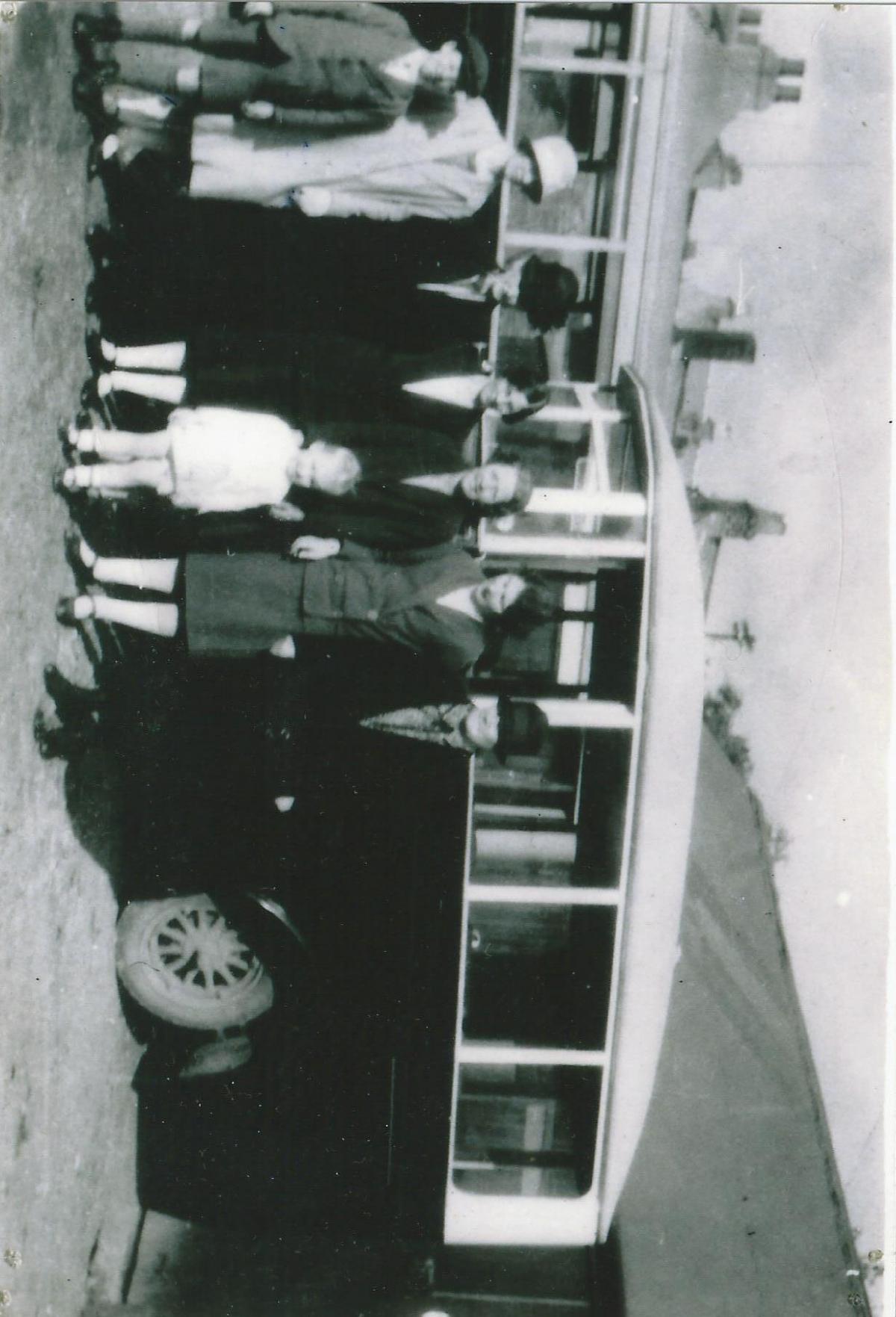

Newbrough resident Mollie Telford wrote in this particular article, which only emerged from papers being sorted after her death last year, that ‘from these small and seemingly inauspicious beginnings was to develop a thriving business, in which the whole family was closely involved.

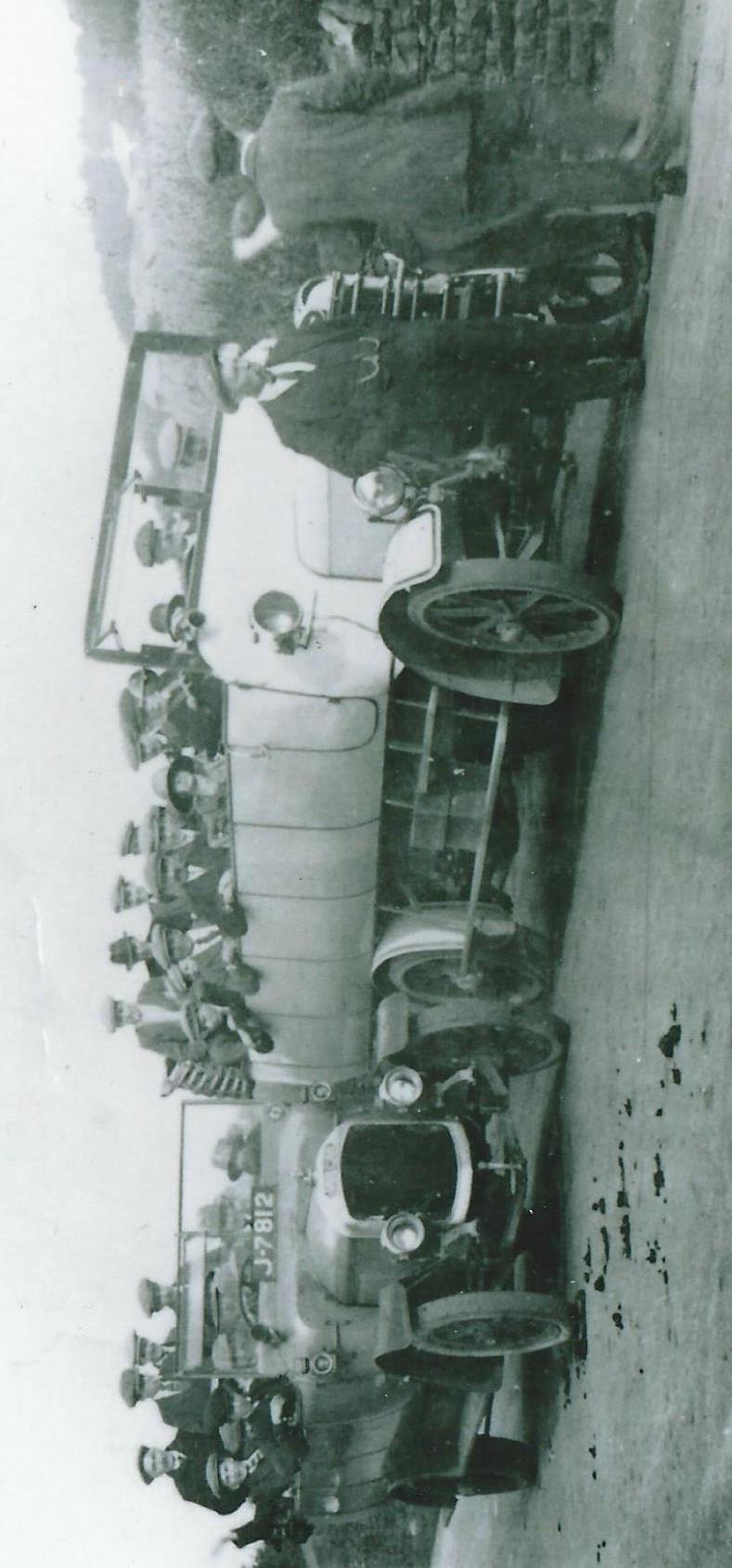

‘Within a few years a fleet of vehicles had been bought and put into service, these early purchases consisting of second-hand lorries and bus bodies.

‘In the late ‘20s and early ‘30s it was customary for lorries used for haulage during the week to be converted for passengers at weekends, when the demand for bus services was greater than during the week.

‘This meant that weekends were exceptionally busy for, at midday on Saturdays, the lorry bodies and wheels were removed from their chassis and replaced by bus bodies and wheels, the whole process being reversed at midnight on Sundays.

‘As buses increased in size and more were purchased, this procedure, of course, became unnecessary.’

The people that were the main passengers in this story, the evolving demands of the industries around them and the changes in law that drove the changing styles of the vehicles required are all investigated in this wonderful article, Buses along the Tyne: the M Charlton Bus Company.

However, Mollie never managed to finish the article. While the bus company in its original form ran until 1961 and then went through a couple of evolutions to become Tyne Valley Coaches, the narrative ends in 1959.

The editor of the Hexham Historian, Mark Benjamin, says: “If any reader would like to research and write up the final chapters of the company’s history, the editor would love to hear from you!”

He would also be delighted if you dipped into the latest edition, with its articles about the legend of ‘The Queen and the Robber’, ‘Ye Battele of Hexhamme in Northomberland’, The Bellman’s Coat, the forested landscape of the late 1700s between the Tyne and the Derwent, the life of ‘People’s Poet’ Wilfrid Wilson Gibson and, finally, the murder of Joe the Quilter.

Hexham Historian is available at the price of £6 from local booksellers.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here